In the movie ‘Number 3’, the main character is Tae-joo (played by Han Suk-kyu), a third-tier gangster. The thing he hates the most is being called ‘Number 3.’ His friend consoles him by saying that reaching Number 3 is a sign of success, but Tae-joo is always dissatisfied with not being Number 2. He understands there’s a significant difference in what Number 2 and Number 3 take home. Whether in leagues or tournaments, a consistent phenomenon emerges as competitions continue: inequality. As the cycle of winning and losing continues, there’s always constant change. However, this change moves consistently in the same direction. There’s a rule to inequality—life is unfair, and it’s all because of competition.

Today’s competition takes place not on battlefields but in markets. What image comes to mind when you hear the word ‘market’? Some might picture diligent people at a dawn market and their bustling activities. Others might think of the vibrant human touch of a traditional market. While one might find the intense scenes of life in these markets beautiful and heartwarming, one cannot deny that underlying these scenes is competition. Broadly, any place where people meet can be considered a market. In this market, we collaborate but also constantly compete, much like the law of the jungle where only the strong survive. Moreover, this market is vastly unfair. In fact, it’s more accurate to say the world itself is unfair.

I’m not just setting out to complain about the world. Let’s acknowledge the reality filled with inequalities we live in. Particularly for those participating in competitive tournaments, despite earning minimal income at lower levels, they continue to play their roles diligently, fueled by the hope of advancing to higher levels. As one climbs these levels, wealth and power increase not just slightly but exponentially. Moreover, once one reaches a higher level, the prestige alone may secure them a permanent spot.

Just as a musician with a single hit song can have a career in the broadcasting industry for life, so it is for politicians, businessmen, and authors once they become famous, ensuring their job security. This is possible because of the numerous participants in their respective tournaments. Thus, such inequality serves as a motivational tool for people. In the end, this results in further deepening of inequality.

The problem is that this kind of inequality exists in our markets and nature as a natural and regular phenomenon.

The Regularity of Inequality

The most plausible explanation for this regularity is what we commonly refer to as the 80:20 rule. This rule was formulated by an Italian economist named Pareto, who observed that 20% of the Italian population owned 80% of the land and generalized this phenomenon into a law. It could be considered the first law of inequality.

Examples of this rule include 20% of all customers generating 80% of department store sales, 20% of competent employees handling 80% of a company’s total workload, and 20% of criminals committing 80% of the crimes. Indeed, this principle can explain many phenomena apparent in most societies and nature.

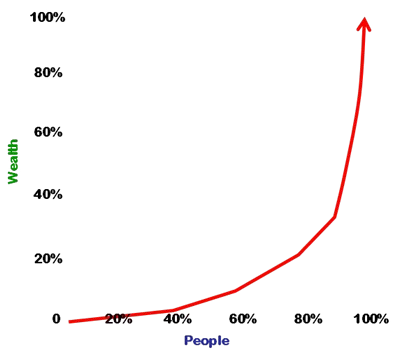

However, the 80:20 regularity is just a part of, or an approximation of, the broader laws of inequality we encounter. Put simply, it’s roughly that proportion. Thanks to scientists studying complex systems, we now understand that the distribution of inequality follows a ‘power law’. To put it simply, whether it be money, power, or influence, the magnitude of these elements doesn’t increase incrementally but rather exponentially.

For instance, if the power of the second-highest political authority is 10, the power of the highest authority isn’t 11 or 12 but rather a multiple of 10, such as 20, 30, or 40. Moreover, if there is only one person at the top rank, there might be two at the second rank, four at the third, and eight at the fourth, meaning the numbers increase exponentially. Thus, the very wealthy possess immense fortunes but are few in number, whereas further down, people’s wealth is only a fraction of this, yet their numbers multiply. This phenomenon is portrayed in the 1997 Korean movie ‘Number 3’, where the protagonist, played by Han Suk-kyu, gets angry when called ‘Number 3’ and insists, “Who says I’m Number 3? I’m Number 2, Number 2,” acknowledging that a step down would significantly reduce his share.

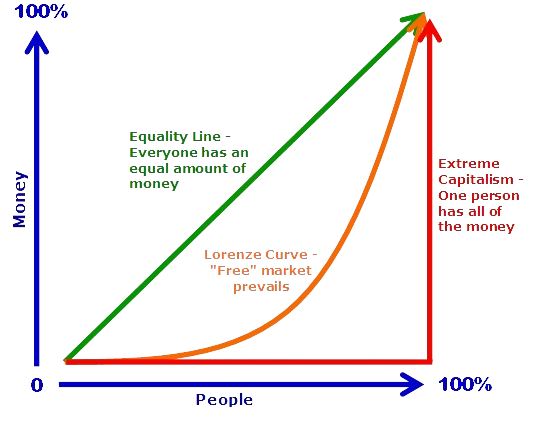

To make this easier to understand, let’s examine the ‘Lorenz Curve’, devised by the American economist M.O. Lorenz. The Lorenz Curve graphically represents the distribution of income in a society by arranging members from those with the lowest to the highest income and empirically showing what percentage of total income is held by the lower percentages of the population.

Let’s imagine a society where all its members are lined up from left to right, starting with the person with the lowest income. Assume that above their heads is displayed the total wealth they possess, not individually, but the combined wealth of everyone in line. If the line includes up to the poorest 10% of the population, the wealth owned by that 10% is written above the head of the last person in that segment. As more wealthy individuals join the line, the total wealth increases, and when the wealthiest join, the wealth reaches 100% and the line of people ends. This scenario is graphically represented by the Lorenz Curve, which essentially shows the cumulative distribution.

For instance, if the lowest 10% of the population held 10% of the nation’s total produced wealth, the lowest 20% held 20%, and the lowest 30% held 30%, then the cumulative distribution of personal income would form a straight diagonal line at 45 degrees across the graph.

Conversely, if one person owned all the wealth in a society, the Lorenz Curve would resemble an ‘L’ shape flipped horizontally. This graph, when plotted with actual statistical data to derive the Lorenz Curve, indicates that the closer the curve is to the diagonal line, the more equitable the income distribution is. The farther it deviates from the line, the more severe the inequality.

The graph above illustrates the commonly discussed 80:20 rule using the Lorenz Curve. As you know, the 80:20 rule, identified by the economist Pareto, is not only about 20% of landowners possessing 80% of the land, but it also manifests in other areas: 20% of key customers generate 80% of sales, 20% of criminals commit 80% of crimes, and 20% of competent employees handle 80% of the work—a law based on empirical observations of inequality.

In reality, the Lorenz Curves of many countries show a similar pattern. For example, the U.S. Lorenz Curve shows a slightly better distribution than the 80:20 rule, but broadly speaking, it is similar. Countries like Sweden and Indonesia see the top 20% owning about 80% of the wealth, while in Canada, Germany, Norway, and France, the top 20% own about 70% of the wealth. In countries like Korea, Australia, China, and Ireland, the top 20% hold about 60% of the wealth.

Globally, the top 1% of the wealthy own 40% of the world’s wealth, and the top 10% of the global population possesses almost 85% of the world’s wealth, indicating a level of inequality even more severe than what the 80:20 rule would suggest.

What about the income within a company? In the U.S. during the early 2000s, the salary gap between a CEO and a regular full-time worker was reported to be around 400 times. CEOs of companies like Merrill Lynch and Lehman Brothers, implicated in the 2008 global financial crisis, managed to bankrupt their companies while still receiving lavish salaries and bonuses. Merrill Lynch’s CEO John Thain received a salary of over $25 million, or 30 billion KRW, in December of the previous year, and Dick Fuld of Lehman Brothers earned 80 billion KRW in salary.

This disparity is not limited to the business world. In the entertainment and sports industries, for instance, an average actor in Korea earns about 400,000 KRW per episode, but Bae Yong-joon received over 100 million KRW per episode for ‘The Legend’ and Song Seung-heon received 70 million KRW per episode for ‘East of Eden’.

In the English Premier League, Chelsea’s Frank Lampard was one of the highest earners, with an income of 40 million pounds (about 90 billion KRW) over four seasons starting in 2008, effectively earning as much as the entire payroll of some Premier League clubs. Film director Steven Spielberg made $165 million in 1994, vastly outearning many of his peers, who are equally talented but earn significantly less, with many directors still struggling to make ends meet.

The problem is that this kind of inequality is not only present in market economies but also appears in planned economies where power inequalities would likely be seen, and in various industries where disparities in size and sales occur. On the internet, website traffic follows this distribution. This type of inequality is also evident in the incomes of individuals in entertainment, sports, and finance. The market always consists of a few giants and many dwarfs, or just a couple of giants while only one dwarf barely manages to survive.

답글 남기기