Let sentences connected!

Go to Korean Version

Explore the Table of Contents

History is mostly the story of victors. However, in movies based on historical events, sometimes the stories of the losers are more interesting. But such movies often contain exaggerated or distorted history. In reality, losers are usually hidden from view.

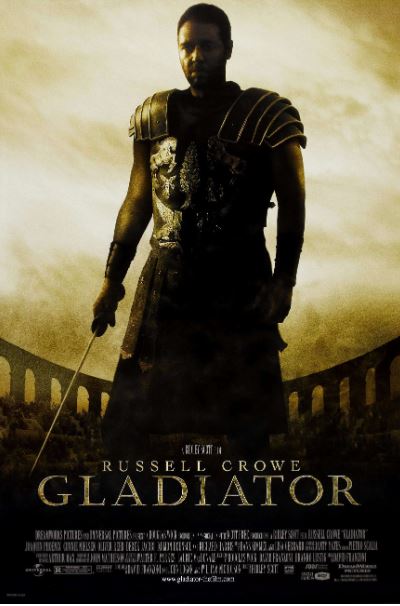

The movie “Gladiator,” produced in the year 2000, is one such film. This movie is one of the first historical dramas set in the Roman era produced by Hollywood since “The Fall of the Roman Empire” in 1964. Indeed, “Gladiator” and “The Fall of the Roman Empire” share the same historical background and characters. In this sense, “Gladiator” can be considered a remake of “The Fall of the Roman Empire.”

The issue is that Maximus, the protagonist of “Gladiator,” and Livius from “The Fall of the Roman Empire,” are the same character but also different. Maximus is killed by the emperor, while Livius successfully assassinates Emperor Commodus. Maximus, who nearly became emperor from a general before ending his life as a slave and then a gladiator, leads a more turbulent life than Livius. The following is a dialogue between Emperor Commodus and Maximus in the movie “Gladiator”:

Commodus: The general who became a slave. The slave who became a gladiator. The gladiator who defied an emperor. Striking story! But now, the people want to know how the story ends. Only a famous death will do. And what could be more glorious than to challenge the Emperor himself in the great arena?

Maximus: You would fight me?

Commodus: Why not? Do you think I am afraid?

Maximus: I think you’ve been afraid all your life.

A sentence is created through various combinations of nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Phrases and clauses formed by connecting multiple words also become one of the elements of a sentence, taking on the role of either a noun, adjective, or adverb.

S + V + (Who + What) + [Where + Why + How + When]

Adjective clauses also include a subject and verb within the clause, which inevitably makes them longer. According to the principle of simplicity we emphasize, long and complex adjectives must follow the noun. English grammar books refer to this usage as relative pronouns.

The general who became a slave. general = who

The slave who became a gladiator. slave = who

The gladiator who defied an emperor. gladiator = who

It’s evident from the expressions above that sentences are formed by first mentioning simple words (general, slave, gladiator) and then adding descriptions. The role of decorating the preceding words is played by clauses led by ‘who’. Therefore, ‘who’ effectively serves both as a conjunction connecting two sentences and as a pronoun. Let’s simplify the complex grammar discussion. Simply put, the noun that is decorated by the relative pronoun, hence called the antecedent, precedes ‘who’.

To reiterate, according to our ‘principle of simplicity’, complex and lengthy adjectives come later. The nouns (antecedents) being decorated by these long adjectives are ‘the general’, ‘the slave’, and ‘the gladiator’, with ‘who’ acting as the pronoun for these nouns.

The type of relative pronoun used varies depending on the antecedent. If the antecedent is a person, ‘who’ is used, if it’s an object or animal, ‘which’ is used. Meanwhile, ‘that’ can be used with people, animals, and objects as the antecedent.

Clarence the Angel: Remember no man is a failure who has friends. <It’s a wonderful life, 1946>

Following grammar rules, the quote should be “Remember no man who has friends is a failure.” However, it’s a famous quote understandable by the principle of simplicity.

MARIETTE COLET: You see, François, marriage is a beautiful mistake which two people make together. But with you, François, I think it would be a mistake. <TROUBLE IN PARADISE Paramount, 1932>

Especially when the antecedent includes superlatives, ordinal numbers, the very, the only, the same, all, every, any, no, etc., ‘that’ is commonly used as the relative pronoun.

Mouse: To deny our own impulses is to deny the very thing that makes us human. <The Matrix>

Among these relative pronouns, ‘What’ includes the antecedent within the word itself and can be replaced with “the thing which∼”, “anything which∼”, or “all that∼”. Whoever, whomever, whatever also include their antecedents within the pronouns.

Supervisor: Attention, whoever you are. This channel is reserved for emergency calls only.

John McClane: No …shit, lady. Do I sound like I’m ordering a pizza? <Die Hard 1988>

Adjective Clauses for Place, Reason, Method, and Time

When a noun (also known as an antecedent) specifically signifies a place, reason, method, or time (this includes specific references to days, weeks, months, or years), clauses using the words where, why, how, and when can serve as adjectives.

While English grammar books may label these as adverbial clauses, it’s more accurate to describe them as extended adjectives. The label ‘adverbial’ is applied to the words where, why, how, and when themselves, not implying that the clauses they introduce are adverbial clauses. Similar to clauses initiated by relative pronouns, these clauses function as adjective clauses. Thus, both relative adverbs and relative pronouns form what are known as relative clauses, which both function to describe the noun they precede.

| antecedents | relative adverb | relative pronoun |

|---|---|---|

| the place | Where | at[on, in] which |

| the reason | Why | in[on, at] which |

| the way | How | in[on, at] which |

| the time, the day, the week, the month, the year | When | in[on, at] which |

John Kinsella: Oh yeah. It’s the place where dreams come true. (Field of Dreams 1989)

Clauses following ‘where’ describe ‘the place.’ The next example shows an adjective clause led by ‘when’ that modifies ‘time’, and the following one shows a clause led by ‘why’ that modifies ‘reason’.

Steven Spielberg: The time when there was no kindness in the world, lives were saved and generations were created. <Schindler’s List>

Gambol: [to The Joker] Give me one reason why I shouldn’t have my boy here pull your head off. <Dark Knight, 2008>

These relative adverbs, similar to relative pronouns, allow for expressions that include their antecedents, such as ‘whenever’ meaning ‘at any time when’, ‘wherever’ meaning ‘in any place where’, and ‘however’ meaning ‘no matter how’.

TOM JOAD: Wherever there’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. <THE GRAPES OF WRATH, 1940>

Such relative pronouns and adverbs also have a continuous usage, useful in speech. When writing, a comma precedes the relative pronoun, and the clause can be interpreted as continuing from the preceding sentence, not just modifying the antecedent but connected as if it’s part of the same sentence. For example:

Jerry: Well, don’t worry! I’m not going to do what you think I’m going to do, which is FLIP OUT! <Jerry Maguire 1996>

‘Which’ refers to ‘what you think I’m going to do’. Although this expression is known as the continuative usage of a relative pronoun, we should interpret and express all relative pronouns in this way. English starts with simplicity and adds explanations, and we need to train ourselves to interpret in this order.

Another point about relative pronouns is that objective relative pronouns like whom, which, and that are often omitted.

Knute Rockne: Tell ’em to go out there with all (that) they got and win just one for the Gipper. <KNUTE ROCKNE ALL AMERICAN: 1940>”

답글 남기기