Robert Ludlum’s bestseller ‘Jason Bourne’ trilogy was successfully adapted into films, starting with The Bourne Identity in 2002, The Bourne Supremacy in 2004, and The Bourne Ultimatum in 2007. The protagonist, Jason Bourne (played by Matt Damon), is a highly trained assassin who loses his memory after an accident. Despite this, Bourne is the first secret agent created by a top-secret organization under the Department of Defense and is aware of CIA conspiracies, making him a target for elimination by the CIA. In The Bourne Ultimatum, CIA Director Ezra Kramer (Scott Glenn) makes a significant statement while ordering Bourne’s assassination:

“My number one rule is hope for the best, plan for the worst.”

The same effort does not always yield the same results. This is because not only do we move, but all other environments around us also change. We continuously strategize, but our surroundings constantly shift, influencing each other. It’s natural for results to vary; sometimes, we get the best outcomes, and other times, the worst. The existence of both best and worst outcomes implies countless possibilities in between.

The world is a continuous fractal, and although composed of several elements, differences are always present. Uncertainty and unpredictability seem to underpin the world. Quantum physicists assert that “the world smaller than an atom is governed by the principle of uncertainty,” to which Einstein retorted, “God does not play dice.” However, quantum mechanics revealed that the small universe composed of electrons operates by the laws of chance and probability, causing Einstein to be mocked for not understanding his own theory of relativity despite presenting it to the world.

In fact, embracing the concept of probability makes the laws of nature seem to work even in an uncertain world. Under identical conditions, the same phenomenon may not always occur, but similar types of phenomena appear, rarely producing something entirely unexpected. When River Phoenix in My Own Private Idaho wonders if everything in the world is different, Song Kang-ho responds that, with proper organization, everything is similar. During the process of classifying different paths into types, we discover patterns.

Recognizing patterns means noticing repetition and understanding the differences, commonalities, and relationships among the elements.

We enjoy relatively simple knowledge about living organisms thanks to the efforts of many ancestors, but we realize that the work of classifying organisms is far from simple. The classification of life forms itself is recognized as a separate discipline, known as taxonomy. A Short History of Nearly Everything cites ‘The Wall Street Journal,’ noting that about 10,000 taxonomists work worldwide, but this is insufficient. Astonishingly, many have dedicated their lives to a single species. Barbara McClintock devoted her life to studying corn, while Jane Goodall lived with chimpanzees to research them, as detailed in her book In the Shadow of Man. These individuals left their names in biological history, yet countless others devoted their lives to seemingly insignificant species like moss or snails.

The reason they focus on one species is due to the incredible variety of qualities each species possesses. Understanding one object or organism fully is extremely challenging because it has numerous qualities. Qualities refer to characteristics or attributes. Organisms and objects have countless qualities, such as size, shape, color, movement speed, sensory degree, and energy absorption methods. Given this, the current phylogenetic tree of biology groups similar entities based on proximity and similarity, though the classification criteria are often inadequate. Various criteria are used, such as movement for animals and plants, photosynthesis for plants and fungi, and the presence of organelles for prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Despite minimal differences in DNA, living organisms exhibit various traits. Classifying them from multiple perspectives aids in understanding nature. Rather than comparing all traits simultaneously, focusing on one trait at a time can be beneficial. For instance, animals can be classified by running speed or size. Although quantifying traits is challenging, concentrating on one trait allows better understanding through statistics. Using statistics alone can simplify the world, as it is a tool for simplification.

Moreover, when comparing the same species instead of different ones, the concept of the average becomes more meaningful. Most natural organisms we encounter exhibit a normal distribution. Even those uninterested in statistics should remember this simple yet helpful concept.

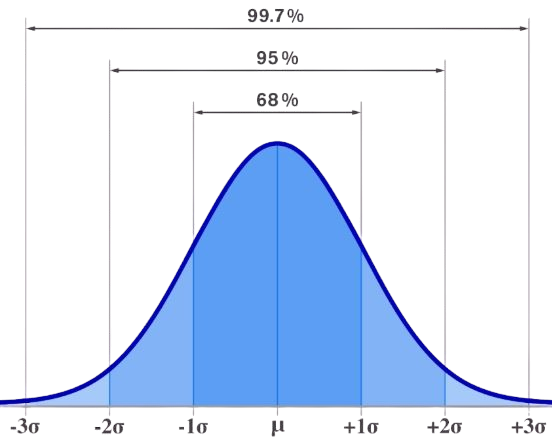

The normal distribution is characterized by most individuals clustering around the mean, with fewer individuals appearing as we move away from the center, forming a bell-shaped curve. Most phenomena observed in nature follow this distribution. For example, human IQ, with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 24, follows a normal distribution. If a value follows a normal distribution, approximately 68% of the data falls within one standard deviation from the mean, and about 95% falls within two standard deviations. Thus, around 68% of people have IQs between 76 and 124, and about 95% fall between 52 and 148.

The mean value is valuable as a representative figure because most observations cluster around it. However, we must also consider the presence of outliers. While lions are generally brave, some might not be. Observing our surroundings reveals these outliers. There are very timid puppies and fearless ones, as well as seagulls like Richard Bach’s Jonathan, who exhibit extraordinary bravery.

Despite this, most live as average seagulls. The same applies to humans. On average, people grow physically and mentally, with declining vision and hearing functions. In natural phenomena with a normal distribution, the mean value can serve as a useful representative. Knowing the average speed of animals, for instance, helps us understand the animal world more simply. We must remember, however, that there are always outliers. As CIA Director Kramer in The Bourne Ultimatum said, we must know the best and worst cases. By understanding the average, best, and worst cases, and the degree of variance, we can develop strategies to respond to observations.

The fastest human in the world runs 100 meters in 9.74 seconds, approximately 37 km/h. If an average adult male runs 100 meters in about 14 seconds, he runs at around 25 km/h. However, humans cannot sustain this speed for long distances. Kenyan marathon record holder Paul Tergat ran 42.195 km in 2 hours, 4 minutes, and 55 seconds, maintaining a steady speed of about 20 km/h. Thus, humans can run at a maximum speed of 20 to 25 km/h. In contrast, the fastest land animal, the cheetah, can sprint at 112 km/h, covering 100 meters in 3 seconds. Antelopes, often prey in Wild Kingdom, can run at 90 km/h, making it difficult for lions, which can run at 70 km/h, to catch them without ambushing or collaborating. For simple curiosity, the average speed suffices, but if capturing a cheetah or escaping a lion is the goal, the situation changes. To catch a cheetah, a car that can reach 112 km/h is sufficient, as not all cheetahs can run at this speed. Conversely, to escape a lion, we need equipment that can surpass 70 km/h because there could be lions faster than the average.

CIA Director Kramer’s advice to “hope for the best, plan for the worst” holds here. Similarly, while we should understand observations by their average, we must also consider the best and worst cases.

The average can be seen as the expected value, representing the most likely outcome among possible future scenarios. The expected profit in a business reflects its characteristics. However, worst-case scenarios can occur in reality. If we cannot cope with or endure such scenarios, the average value becomes meaningless. Conversely, during business operations, maintaining a positive and proactive attitude while expecting the best results is crucial. This perspective can apply to academia, policy, and daily life. While the average provides important clues for understanding the world, in reality, we often need to focus on expectations safer than the average. For example, economics assumes rational humans, who are neither swayed by emotions nor make calculation errors. In essence, only very intelligent people inhabit the world of economics. Yet, as we acknowledge, real people are not always rational. On average, most people lack the rationality economics assumes. Nevertheless, assuming rationality provides a safe hypothesis in markets, as irrational individuals do not significantly affect results when many people collectively determine prices. Hence, despite the presence of irrational individuals, theories based on rationality can explain social phenomena.

The same applies to human selfishness. Most people have both selfish and altruistic aspects. Likely, most people exhibit a balance of these traits, which constitutes the average. However, in everyday life, we must tune into people’s selfishness. Although saying “humans are selfish” does not represent the average, it serves as a practical, risk-free hypothesis about people. Imagine laws and systems based on altruistic individuals. Selfish individuals might benefit while altruistic ones find life increasingly challenging.

Consider thinking of someone as selfish. Believing this does not cause major issues in our lives. We would appreciate anything they offer, recognizing it as generosity from a selfish person. This mutual gratitude and giving can foster a positive relationship. Conversely, if we assume someone is altruistic and they turn out to be selfish, we might feel hurt and resent them. Even if they are highly altruistic, we may not feel grateful, having expected their generosity.

Thus, while the assumption that humans are rational and selfish might not reflect the average, it becomes a necessary wisdom for studying and living daily life. Applying CIA Director Kramer’s words from The Bourne Ultimatum to our lives means “hoping everyone is good while preparing for the possibility they might be bad.”

답글 남기기