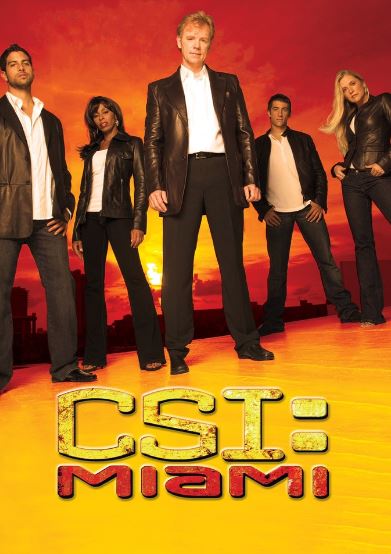

The American drama series CSI, which began in 2000, initially set in Las Vegas, was followed by CSI: Miami and CSI: New York. Reflecting its sustained popularity, the series garnered significant following not only in the United States but also in Europe and Korea. Unlike Columbo, which solved cases with extraordinary deductive reasoning and tricks, CSI employs all scientific investigative techniques, such as DNA testing, laser-based ballistic tracing, and computer simulations. Naturally, the team leaders must be armed with scientific knowledge. The lead characters Grissom (Las Vegas), Horatio (Miami), and Mac (New York) are all ‘Level 3’. Level 3 is the highest qualification for crime scene experts certified by the International Association for Identification (IAI), requiring publications or books in the relevant field, over six years of field experience, and at least one year of training new investigators. The show’s leaders prioritize evidence based on cold judgment and scientific analysis. However, finding perfect evidence at a crime scene is challenging. Therefore, these forensic teams strive to fill in the gaps, making the show truly engaging. Particularly, Horatio in CSI: Miami trusts his intuition.

“Science! It helps investigate crimes but doesn’t determine who the perpetrator is. I trust my intuition and imagination, expecting science to confirm it.”

Despite various measurement tools and computers capable of analyzing even the smallest evidence left at the scene, fully recreating a crime scene without a confession or eyewitness is difficult. Investigators must find the link between the reality of the crime and the observed and analyzed data. Horatio believes that intuition and imagination are the keys to finding this link.

Robert Root-Bernstein points out that what we perceive directly through our senses, such as sunrises, sunsets, photographs, drawings, or scribbles on paper, is not the true reality. In the movie The Truman Show, the director of the show, Christophe, emphasizes during an interview, “We accept the reality of the world with which we are presented.” Indeed, what we see is not the real thing. In an empty space, electrons are merely swirling around. However, we should not dismiss everything we see and touch as unreal. That would be overly abstract, and since we all share the same illusion, recognizing it as reality does not pose significant issues. We must acknowledge, though, that we do not see the whole reality at once.

The first task in understanding our environment has always been analysis, breaking down and observing elements. This process reveals part of the world, but the analyzed results alone cannot fully grasp its essence, as much information might be lost in the process. Most objects in our world are interconnected, with their components interacting. If you split water into two containers, you get two sets of water, but further division yields hydrogen and oxygen, which bear no resemblance to water. Timid individuals can form an angry mob, and moral individuals can create an immoral society, as the characteristics of members disappear, leading to provocative, violent behavior due to their interactions. Finding this hidden connection requires imagination. Thus, interpreting analyzed and organized data to truly understand a subject necessitates the imaginative power discussed in ‘knowing oneself’.

Aristotle defined historians as those who speak of actual events, while poets talk about what might happen. The difference lies not in the presence or absence of rhythm but in the recounting of ‘occurred events’ versus ‘possible events’. Imagination itself is a form of creation. It is necessary not only for writers but also for readers who interpret the created worlds, forming their own unique worlds and deriving different experiences. Poetry and novels are products of imagination, yet reading them also demands imaginative effort.

However, imagination is not confined to literature. Historians, too, require imagination. Limited historical records and artifacts necessitate the discovery of relationships between fragments through imagination. This hypothesized relationship must then be scientifically validated. This applies to all social sciences, and even natural sciences. Though reasoning might seem illogical, it is essential for peering into an incomplete and inaccurate world, linking the known and the unknown.

As a technique for classification, we recommended the logic tree, a method of categorizing information starting from broad classifications and progressively branching into subcategories. This deductive approach infers specific details from general knowledge. If we don’t already know something, creating a logic tree structure is impossible. In such cases, classification must proceed in reverse, as we lack the knowledge for broad categorization.

When little is known about the subject of observation, we have no choice but to group similar items. Patterns and types eventually emerge, a process known as inductive reasoning. Inductive reasoning derives general truths from specific observations. For instance, observing that all crows seen so far are black allows us to conclude that all crows are black. This method aids in expanding knowledge and offers a sense of realism as it is based on concrete world experiences. However, inductive reasoning can be flawed, as generalizations from limited experiences may be incorrect. If a white crow is discovered, the generalized conclusion that “crows are black” is invalid.

Knowledge and theories evolve through such trial and error.

Most imagination progresses in an inductive manner, as humans are adept at recognizing patterns and generalizing from a few experiences. Our everyday conversations over tea often employ inductive reasoning, creating stories from morning commutes. Novelists excel in this, crafting moving narratives from individual experiences. Historians can produce detailed series from a few historical fragments. The historical records about Dae Jo-yeong, for example, are scant, yet novelists can create extensive works like a 134-episode series. Imagination bridges reality and fragmented information.

Understanding the unseen and unheard also relies on imagination. In nature, there are elements beyond human sensory perception that can be inferred from observed effects. Estimation, essentially, is imagination. Even complex, obscure phenomena become clearer through imagination.

Observation is the most fundamental method for understanding the world. Early scientific knowledge accumulated through active observation, discovering and verifying patterns. Highly skilled individuals can possess senses beyond the ordinary, honed through training and experience. For instance, a textile dye expert can distinguish numerous color variations, and master violin or piano makers likely had exceptional auditory perception. Wine tasters possess refined taste recognition abilities. However, such abilities have limits.

Humans hear within a frequency range of 16Hz to 20,000Hz. Visible light for the human eye, or the visible spectrum, ranges from approximately 380nm to 760nm. Infrared and ultraviolet light outside this range are invisible to us. The visible spectrum’s dominance in sunlight reaching the Earth’s surface might explain our eyes’ sensitivity to this range due to evolutionary adaptation. Humans have endeavored to surpass sensory limits, expanding their bodies’ capabilities. Microscopes reveal the tiny world unseen by the naked eye, while telescopes make distant objects observable. Yet, even with these tools, our eyes must perceive the information.

Our brains, too, have limitations in perceiving time and space. For example, we can roughly gauge time without a clock, sensing hours and days, but accurately knowing weeks or years relies more on cognition than sensory perception. Thus, people often lament losing track of time. Our maximum perceivable duration might be the universe’s age of 13.7 billion years, beyond which we refer to as ‘infinity’ or ‘eternity’. The shortest created time is 10^-15 seconds, with the theoretical minimum being Planck time at 10^-43 seconds. In daily life, we ambiguously refer to the briefest moment as ‘instant’. Nevertheless, the smallest perceivable time unit in reality is the ‘second’.

Considering space, comparing relative sizes from atoms to galaxies is challenging. Fortunately, logarithmic functions allow representing such a vast range of sizes on a single line. This requires imagination. Each increment on a regular scale signifies multiplication; for example, from 1m to 2m means doubling. On a logarithmic scale, each increment signifies tenfold, making two increments a hundredfold. Familiar life forms range between 1m to 10m. Understanding sizes from human proportions is straightforward, but comprehending Earth’s diameter of over 10,000km (10^7m), the Sun’s size 109 times that of Earth (10^9m), or the distance of one light year (10^13m) is nearly impossible without imagination.

On the smaller scale, biological cells, including bacteria, are about 1 micrometer (10^-6m). Beyond this, 10^-10m reveals atoms, marking the minimum size for meaningful substance manipulation. Further division reaches atomic nuclei and particles like electrons and protons at 10^-15m. Theoretical divisions might go smaller, but Planck length (10^-36m) marks a fundamental limit, as the concept of space itself changes. Similar to absolute zero temperature (-273°C) and the speed of light (300,000 km/s), reaching such extremes requires imagination.

As we delve into dimensions, it becomes even less natural. The space we perceive is three-dimensional. Adding just one dimension to the known concept of time makes it difficult for us to understand and express it. This is because we cannot think of or see dimensions higher than the one we live in. For example, imagine there are lines living in a one-dimensional world. If a two-dimensional plane enters this world, how would the lines perceive the plane? They could only see it as a line. The same phenomenon occurs in the world of planes. When a three-dimensional object enters a two-dimensional world, it won’t be seen as a solid object but only as a plane. However, its area would appear irregular and uncertain. If all the faces of the solid are not identical, the length or area will appear differently depending on its movement. Therefore, the existence of a solid in the world of planes always becomes an uncertain and changing entity.

This might be why we do not fully understand this world. For similar reasons, it is difficult for us to comprehend principles like relativity, which integrates space and time, or the uncertainty principle of quantum mechanics. Ultimately, understanding this world without imagination is not easy. Unless we deceive our brains, which are accustomed to a three-dimensional world, into thinking that the world is four-dimensional, it requires imagination to create such a deception.

One effective way to enhance imagination is empathy, as mentioned in discussions about observation. To understand history, it is necessary to view the world from the perspective of people in the past. We need to understand not only their thoughts but also their emotions. By immersing ourselves in the standpoint of people who lived in the past, we can grasp their motives and viewpoints related to historical actions and share their emotions. Biologists also need such imagination. A person researching freshwater fish might occasionally need to imagine themselves as a freshwater fish, asking where they would go to avoid deteriorating water quality and aggressive imported predators.

Another way to exercise imagination is through a type of hypothesis where we consider nonexistent things as real and real things as nonexistent. This hypothesis can be called ‘Make Believe.’ Renowned soprano Sumi Jo recalls in her book My Life, My Own Melody that she enjoyed “make-believe play” as a child, a concept she discovered while reading A Little Princess. You might remember that the protagonist, Sara, is suddenly sent to the attic after her wealthy father’s sudden death. However, she continues to live as a princess through her ‘make-believe play.’ She invites a friend to her dirty room and says, “Imagine the floor is covered with thick, soft velvet from India, and there is a cozy long chair in that corner.” This is Sara’s ‘Make Believe Play.’ This hypothetical play that children use is also a method of thinking used in scientific research. We call such methods hypotheses, which form the basis for creating theories.

답글 남기기