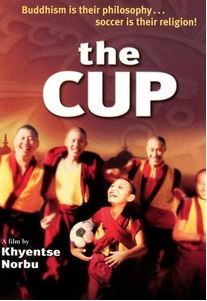

After leaving Tibet, occupied by China, Palden and Nima head to a monastery in the Himalayas. The solemnity and reverence we expect from such a place are absent due to the soccer fever. The monks read scriptures with their mouths, but their eyes are on sports magazines. The walls of the monastery are covered with photos of soccer stars from various countries and graffiti like “Go Paraguay” and “Go Germany.” This is the setting of the 1999 movie “The Cup.” Directed by Bhutanese filmmaker Khyentse Norbu, known for his depiction of Tibet at the edge of the world, the film features Tibetan monks who appear as actors. It is based on the real-life enthusiasm of Tibetan monks for the World Cup. Towards the end of the film, the head monk gathers the young novice monks and gives them a lesson.

Head Monk: Should we cover the whole world with leather to feel softness when we walk?

Novice Monk: No.

Head Monk: Then what should we do?

Novice Monk: I should wear leather shoes.

Head Monk: Yes, wearing leather shoes will make everywhere soft for you.

The head monk then provides an interpretation of this lesson:

“Wearing leather shoes on one’s feet has the same effect as covering the whole world with leather. Everything in life is like this. The world is filled with enemies, adversaries, demons, and all sorts of harmful things. It is impossible to defeat them all one by one. However, if you can calm your own mind, you can control your feelings of revenge, hostility, temptation, and evil thoughts, which is like defeating all the evil things in the world.”

While there is joy in the pursuit of knowledge or enlightenment itself, we all acquire knowledge for a successful daily life. These accumulated pieces of knowledge blend with our experiences to produce wisdom. We too seek such wisdom by simplifying ourselves, nature, and human society. This process comprises knowing oneself (知己) and knowing the enemy (知彼). All this is preparation for venturing into the world and taking action. But there is still one more process left: integrating knowing oneself and knowing the enemy. There are no problems without conditions, no competition without opponents, and no choices without restrictions. Everything that is not oneself determines one’s environment, and for others, one’s existence influences their conditions in some form. Knowledge without integration is useless for life regardless of its quantity.

By integrating knowing oneself and knowing the enemy, we must establish principles and strategies to venture into the world and act. Principles in life are fundamentally reinforced by one’s perspective on oneself and the world. Principles reflect our values and serve as standards for the choices we make in life. Strategies must not deviate from these principles to be effective. The head monk in “The Cup” discusses the nature of strategy and an aspect of a good strategy: changing oneself, like wearing leather shoes, rather than changing the world. Such is the nature of strategy. Strategy involves creative thinking that arises from understanding others and knowing oneself. This strategic thinking has been emphasized since the times of Sun Tzu and is still relevant in our digital economy.

Eastern philosophy has long emphasized such understanding of oneself and the enemy. Daoism (道家) represents the principles of nature (道), and virtue (德) means living in harmony with these principles. When combined, they form morality (道德). If the principle (道) is flawed, virtue (德) becomes useless, and morality becomes rigid and awkward. Eastern thought generally views nature as something to harmonize with rather than challenge. The world and humans are one, living in harmony and balance. In contrast, Western thought often sees nature as something to conquer and constantly challenge. However, balancing this challenge is also strategic, as one cannot always be aggressive but must sometimes take an offensive stance.

Humans have adapted and sometimes challenged their environment to sustain their lives. As British historian Arnold Joseph Toynbee put it, our life is a history of “Challenge and Response.” During the long Paleolithic era, humans gradually improved their lifestyle by discovering fire and making tools while living a life of gathering and hunting. They observed that discarded plant seeds could sprout and bear fruit, which led them to favor farming over constant movement for food. Instead of chasing prey, they tried taming wild animals within enclosures. This agricultural revolution, starting around 10,000 years ago, coincided with the end of the last Ice Age, suggesting that agriculture and livestock farming were responses to environmental changes.

Changes in climate causing prey to move elsewhere and population growth leading to food shortages were among such changes. Humanity thus moved from merely adapting to nature to challenging it. Historians named this first great change in human history the agricultural revolution.

Futurist Alvin Toffler calls this agricultural revolution the First Wave in his book “The Third Wave.” The title suggests that new waves continue to wash over humanity, driven by our spirit of challenge. After the First Wave, humans continued their challenges and responses, finding hidden elements of nature and creating things not found in nature. Discoveries and inventions mark the history of science and human history. The invention of the steam engine triggered the Industrial Revolution, changing production methods and bringing material abundance, marking the Second Wave. As Toffler notes, we moved from agricultural routines to urban life, becoming production workers in factories filled with machines. This revolutionary change was short-lived. After about 300 years, we broke through the Second Wave characterized by mass production and standardization, living in the faster-paced world of the Third Wave. The information revolution has expanded individual social participation and freedom of choice, allowing us to live in a diverse and pluralistic society. However, competition has intensified, requiring us all to be knowledge workers to survive. Future changes are unpredictable and difficult to define in one word, but they will surely align with human desires. The agricultural and industrial revolutions were driven by survival needs for more food and materials, while the information revolution accelerated by personal desires for social participation and growth. Future changes will move towards fulfilling new social desires and self-actualization needs.

With each new wave, not only did our lifestyles change, but the types of knowledge required for survival and growth also evolved. Sun Tzu’s “know yourself and know your enemy” (知彼知己) refers to the enemy (彼) as the opponent in battle. If we classify “know yourself and know your enemy” in versions like the globalization and information age, version 1.0 would be filled with knowledge for survival and struggle. As we transitioned from one-on-one combat to competition with many, the need to outdo others and grow faster expanded. This competitive “know yourself and know your enemy” could be called version 2.0. Today, in the network era, the enemy (彼) is no longer just a competitor. Thus, version 3.0 must include knowledge for cooperation and collaboration. Looking ahead, version 4.0 should consider the welfare and wisdom of the disadvantaged and the deteriorating natural environment.

The disadvantaged, as described by Thomas Friedman in “The World is Flat,” are the “sick,” “helpless,” and “frustrated” people still existing in our global village. Everything is interconnected, influencing each other. The world is increasingly complex and interconnected, a phenomenon called globalization. Human networks have become more intricate and expansive, resulting in a network explosion. While past globalization was driven by states and multinational corporations, today’s globalization is driven by individuals and powered by software like the internet rather than hardware like military force, railroads, or phones. These connections make us neighbors.

We realize we live in a complex world. As discussed, the world comprises numerous components interacting with each other. New phenomena and orders emerge from these interactions, called emergence in complex systems science. Like hydrogen and oxygen forming water, a non-flammable substance, unrelated causes can produce new results. As part of this complex system, we not only adapt to the current environment for our benefit but also predict and initiate changes. It’s not just about having knowledge and creating strategies; others also develop strategies in response to ours. As we execute our strategies, others adapt theirs, influencing our environment and creating further changes. We evolve with our environment, which is itself evolving as a complex system. Change within a system results from the adaptation of its components, and this adaptation and diversity keep the complex system in flux. Individual efforts create waves of change that then impact us.

Despite frequent mentions, not everything is chaotic. While there are times of explosive change, stable periods of equilibrium also exist. We generally experience gradual changes, a world where predictions can be made with probabilities. Though we cannot face the world with definite answers, we can increase our chances of success through decisions and actions. Knowing oneself and knowing the enemy aims to find strategies and principles that raise the probability of success.

We cannot succeed in everything nor need to. Most people get ample opportunities to succeed once. There’s no need to rush ahead. Despite the emphasis on change as a virtue, there’s no clear evidence that frequent change leads to victory. Basic human needs remain constant despite changes. Consistent effort leads to achievements, regardless of scale. Avoid the delusion of creating everything alone or all at once. Even significant creations are built on predecessors’ foundations, often following others’ work. There’s no need to do it alone. Successful people always have collaborators. Sharing joys and sorrows with others is a condition for happiness.

Bob Young, founder of Red Hat, a company that succeeded with Linux solutions, asserts, “No one in this world is useful as a loner.” In “The Opposable Mind” by Canadian management professor Roger Martin, based on interviews with 50 exceptional leaders, Young emphasizes that his story is a “top secret.” However, the desire to excel in everything should be seen as excessive ambition. In today’s fast-changing, competitive world, there are few things one can do alone. By giving up what one can do, one can gain something truly valuable. As George Leonard suggests in “Mastery,” one must always train and prepare. Constant execution might be necessary. Leonard describes the path to mastery as:

“Stay on the long road to mastery!”

답글 남기기