Speaking with the principle of simplicity

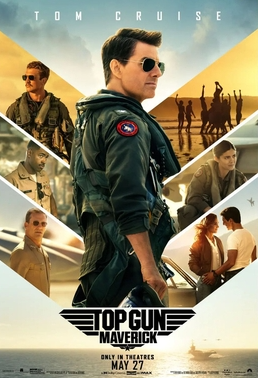

The movie Top Gun (1986) depicts the love and friendship among fighter pilots. “Top Gun” originally means “the best marksman (or hunter)” and is also the name of the U.S. Navy’s aerial combat school (officially called the “Navy Weapons School”). It’s said that the title of “Top Gun” is awarded to pilots who graduate from this school with the highest honors.

The pilots in the movie are all pranksters. They don’t hesitate to tease their instructor with lines like:

Maverick: It’s classified. I could tell you, but then I’d have to kill you.

However, what the main character and his friends truly enjoy is “speed.” All the members returning from flight enjoy the following line, shared between the protagonist and his sidekick:

Maverick: I feel the need… Maverick, Goose: …the need for speed!

The basic principle of English is to start with the conclusion in the form of <subject + verb>. This structure answers questions by following the sequence of the English syntactic order. If you only know nouns, simply listing them in our syntactic order after the verb can somewhat convey the meaning. However, what should we do when the words we want to express do not end with a single noun?

In fact, if the subject and verb consist of just one noun and one verb, English would be much simpler. But that would also mean losing richness in expression. Just as several words come together to act as one verb, nouns also receive support from multiple words to create more sophisticated and accurate descriptions. The principle that applies here is simplicity. That is, start with the simple and gradually add complex explanations. This method is also a result of their way of thinking, starting with the conclusion and then adding details.

Maverick first says, “I feel the need.” Then, he completes his expression by adding that the need is for speed. It’s a way of expressing by starting with something simple and then adding more detailed explanations. Similarly, Forrest’s mom said, “I did the best I could.” She starts by stating she did her best, then explains what those best entails. Although we haven’t discussed adjectives directly, English begins with short expressions and adds complexity for effective communication.

Thus, nouns usually form a group with the help of various parts of speech to function as a noun. In grammar, such a group is called a noun phrase. Anyway, a noun phrase typically has the following structure:

Noun Phrase = Article + Adjective + Noun + Adjective Phrase

Simply put, while simple adjectives can modify a noun before it, longer adjectives are more naturally placed after the noun to modify it. Consider Max’s words from The Sound of Music:

Max: I like rich people. I like the way they live. I like the way I live when I’m with them. <The Sound of Music>

The reason we haven’t had issues discussing adjectives directly is that the use of adjectives in English isn’t significantly different from Korean. In short, it’s natural. Just like ‘rich people’, where the adjective modifies the noun before it. The issue arises when the adjective becomes longer or more complex. When saying ‘the way rich people live’, Korean still places the modifier before the noun. But in English, it must go after the noun. That is, “start with the simple and gradually add complex explanations!” is the principle of simplicity in English to create English-like sentences.

Richard ‘Rick’ Blaine: Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship. <Casablanca>

To express ‘the beginning of a beautiful friendship’ in Korean, we first mention a beautiful friendship, then the beginning. However, in English, ‘beginning’ is stated first, followed by solving the curiosity of “what beginning?”

John Keating: There is a time for daring and a time for caution, and a wise man knows which is called for. <Dead Poets Society>

Again, the noun complement ‘time’ is mentioned first, and what kind of time it is, is explained later. A time for daring, a time for caution. In English grammar, a group of two or more words that modifies a noun, as in the example above, is called an adjective phrase. When multiple words come together to modify a noun, they naturally decorate the noun from behind, not the front. Such adjective phrases often come with prepositions, take the form of an infinitive with ‘to’, or are made up of participles.

Adjective Phrases Using Participles

Though we haven’t delved into it specifically, there exists a concept called the passive voice in English grammar. Simply put, it’s used not when the subject is actively doing something but rather when the subject is passively experiencing something. For example,

Sid: I’ll ignore the implication of the question, detective. <CSI New York, Long Run>

The passive voice of this verb is simply formed with “be verb + past participle.

ALEX FORREST: I won’t be ignored, Dan! <FATAL ATTRACTION>

If a past participle form of a verb modifies a noun, it can be thought of as a shortened form of the passive voice.

John Keating: Robert Frost said, “Two roads diverged in the wood and I, I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference.”

In ‘one less traveled by’, “one” refers to a road. “Less traveled by” is an adjective phrase meaning “less frequented by people” and can be considered a shortened form of the passive voice sentence “The road is less traveled by people.” From a simpler perspective, the verb in its passive form acts as an adjective. In fact, not only past participles but also present participles in the progressive form are used as adjectives. Therefore, it’s reasonable to think of participles as verbs tagged to function as adjectives.

Thus, both present participles formed by adding “ing” and past participles formed by adding “ed” to the base form of a verb are adjectives made from verbs. The difference between them is that present participles, as adjectives, imply an active meaning, while past participles, as adjectives, convey a passive meaning. Being adjectives, participles can modify nouns or act as complements just like other adjectives.

CAPT. OVEUR: You ever seen a grown man naked? <AIRPLANE!, 1980>

There are cases where a verb in passive voice entirely becomes an adjective.

BERT GORDON: Eddie, you’re a born loser. <THE HUSTLER, 1961>

“A born loser” means someone who is inherently a loser. Here, “born” functions as an adjective meaning “innate” or “inherent.” As with all rules, there are exceptions; some adjectives can never precede a noun and always modify the noun from behind. These are mostly adjectives beginning with “a,” such as afraid, awake, ashamed, aware, asleep, alive. These adjectives cannot modify a noun before it. However, they can be used after a “be” verb to describe the subject.

FRANKENSTEIN: It’s alive! It’s alive! (Seeing the monster come to life) <FRANKENSTEIN: 1931>

Conversely, adjectives like mere, inner, drunken, wooden, golden, upper, outer, only, elder, former appear only before a noun.

CARL SPACKLER: Cinderella story. Outta nowhere. A former greenskeeper, now, about to become the Masters champion. It looks like a mirac…It’s in the hole! It’s in the hole! It’s in the hole! <CADDYSHACK>

답글 남기기