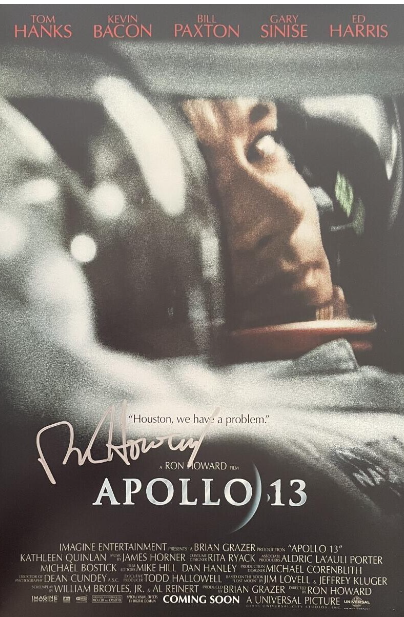

Jim Lovell’s phrase, “Houston, we have a problem,” famously uttered by Tom Hanks in his portrayal of an astronaut in space, has gone beyond its movie origins to become a common saying in America when facing difficulties. This raises the point: is Houston known for solving problems?

The movie “Apollo 13” brings to life the intense space emergency of 1970, captivating not just the astronauts on the doomed spacecraft but also viewers worldwide watching on their TV screens. Launched on April 11, the mission faced a critical setback on its third day due to an oxygen tank explosion, putting the crew’s lives at risk. The story vividly recounts their dangerous return to Earth, emphasizing the teamwork needed to prevent a catastrophe in space and on the ground.

Houston refers to the Johnson Space Center in Texas, the center of U.S. manned space missions, and “Houston, we have a problem” became the distress call from Apollo 13’s crew to report an unexpected technical issue, essentially a call for help.

What began as a statement in a life-or-death situation has turned into a casual phrase used humorously for minor problems or when asking for help. Phrases like “Houston, we have a real problem” for serious issues, “Houston, we don’t have a problem” to indicate everything is fine, and numerous parodies have spread through popular culture, appearing in different movies and TV series.

Despite its dramatic presentation, “Houston, we have a problem” slightly alters the actual words spoken during the Apollo 13 mission, which were “Okay, Houston, we’ve had a problem here,” said by astronaut Jack Swigert. Nevertheless, the phrase has become embedded in popular memory as a symbol of facing and overcoming challenges.

When a subject is followed by a linking verb, such as a form of “to be,” it typically prompts questions like “Who is it?” “What is it?” or “How is it?” Conversely, when a transitive verb follows the subject, it sparks curiosity about “Who?” or “What?”

In reality, whether a verb is intransitive or transitive is a secondary consideration. Once a verb appears and its meaning is understood, it naturally leads to the following sequence of inquiries. It’s important to highlight that once a conclusion is drawn from the subject and verb, the focus primarily shifts to people and then to objects. However, the concept of personification in language means that sometimes, objects or animals that are treated with interest like humans can take precedence. But with transitive verbs, the expression in English becomes straightforward, merely a sequence of words.

S + V + (Who + What) + [Where + Why + How + When]

The very name “transitive verb” implies an action being transferred to a direct object; thus, a direct object is necessary. Verbs that depict actions involving a target, typically involving people or animals, are classified as transitive verbs. With such verbs, we can create simple and efficient expressions. Indeed, even iconic movie quotes are composed of succinct sentences.

DR. PETER VENKMAN: We came. We saw. We kicked its ass. (Ghostbusters, 1984)

HARRY CALLAHAN (Clint Eastwood): Go ahead, make my day. (Sudden Impact, 1983)

RHETT BUTLER: Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.

This line is from Rhett Butler as he leaves Scarlett behind in Gone with the Wind. “Damn” is a transitive verb typically used in the sense of “to curse” or “to criticize harshly.” When “damn” becomes a noun, it denotes a curse or an insult. “Don’t give a damn” translates to “not even willing to curse,” essentially meaning a lack of interest, or “It’s none of my business.”

VIVIAN RUTLEDGE: I don’t like your manners.

PHILIP MARLOWE: I’m not crazy about yours. I didn’t ask to see you. I don’t mind if you don’t like my manners. I don’t like them myself. They’re pretty bad. I grieve over them long winter evenings. (The Big Sleep, 1946)

Like the following examples of transitive verbs, they can take not only nouns meaning “who?” or “what?” but also phrases denoting “doing something” or “the fact that.”

Geoffrey: I know. You know I know. I know you know I know. We know Henry knows, and Henry knows we know it. We’re a knowledgeable family. (The Lion in Winter)

“See,” “watch,” and “look” may have slightly different meanings, but in our language, they all translate to “to see.” Let’s examine these expressions.

Shannon Christie: Am I beautiful at all?

Joseph Donnelly: [whispering] I’ve never seen anything like you in all of my livin’ life. (Far and Away, 1992)

NED ‘SCOTTY’ SCOTT: Watch the skies, everywhere, keep looking! Keep watching the skies! (The Thing from Another World, 1951)

FERRIS BUELLER: Life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it. (Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, 1986)

The verbs “see” and “watch” naturally take an object with the meaning of “to look at.” In contrast, the verb “look” cannot have an object by itself. To take an object, it requires the help of a preposition, as in “look around.” By attaching a preposition, it forms a structure akin to the object marker “~을” in Korean, essentially turning an intransitive verb into a transitive one through the use of prepositions or other means.

JERRY: Look at that! Look how she moves. Some Like It Hot (1959)

In English, there are intransitive verbs that are interpreted as transitive verbs in Korean. These verbs require a preposition to take an object. For example, verbs like look, listen, smile should be naturally translated into Korean as performing an action on something. However, according to English grammar, intransitive verbs cannot have an object, thus they take an object through prepositions. It shouldn’t be confusing. In fact, one can simply perceive <verb + preposition> as a single verb unit.

COUNT DRACULA: Listen to them. Children of the night. What music they make. (DRACULA: 1931)

Additionally, verbs that can be mistaken for transitive verbs but are actually intransitive and require a preposition include “Look at ~””Reply to ~””Wait for ~” for “Graduate from ~” “Interfere with ~” and “Sympathize with ~.” In other words, these verbs need the assistance of prepositions. Once these verbs take a preposition, they can function as transitive verbs, and our questions can be resolved following the order of Korean syntax.

Transitive verbs, as mentioned above, can take an object following the verb. However, there are transitive verbs in English that might not be directly translated into Korean as having an object marker ‘~을’ or ‘~를,’ potentially causing confusion as intransitive verbs. For example, the Korean expression for “to enter somewhere” feels intransitive. A suitable English verb for “to enter” is “enter,” which can be used as an intransitive verb but typically takes an object denoting a place without the need for a preposition.

Reporter: Apollo 13 – lifting off at 1300 hours and 13 minutes, and entering the moon’s gravity on April 13th. <Apollo 13>

Thus, verbs like attend, enter, reach, approach, leave, address, inhabit, and answer can be mistaken for intransitive verbs because their objects translate to “~에,” “~에게,” or “~으로” in Korean. Other verbs like survive, marry, match, join are also transitive verbs that can take an object. For instance, the correct expression is “join me,” not “join with me.”

PVT. JUDY BENJAMIN: I did join the Army, but I joined a different Army. I joined the one with the condos and the private rooms. (Private Benjamin 1980)

J.J. Hunsecker: Match me, Sidney.

Sidney Falco: Not right this minute, J.J. (Sweet Smell of Success 1957)

답글 남기기