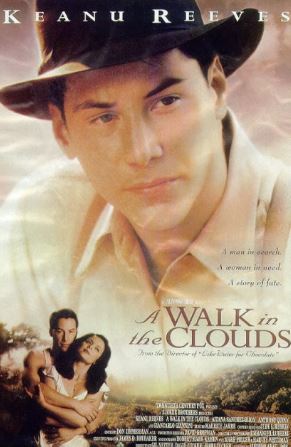

A Walk in the Clouds (1995) is a heartwarming movie. The protagonist, Paul Sutton (played by Keanu Reeves), is an orphan who grew up lonely. After spending three years at war, Paul becomes a chocolate salesman and sets off on a journey, where he meets Victoria by chance on a train. Victoria is a young woman who became an unwed mother while studying abroad and was too afraid to return home because of her strict father. Paul decides to help her and accompanies her to her family’s vineyard, named Las Nubes, which means “The Clouds.”

Victoria’s conservative and strict father treats his daughter coldly for getting married without the family’s approval, and Paul, feeling sorry for Victoria, delays his departure day by day. Gradually, Paul begins to be accepted as part of the family by the other members. One day, a mistake by Victoria’s father causes the vineyard’s grapevines to burn down, leaving the family devastated. At this moment, Paul discovers an unburnt vine from the descendants of the grapevines brought by Victoria’s ancestors, rekindling the family’s hope. Victoria’s father, Argon, grants Paul permission to marry his daughter. While having Paul plant the surviving vine’s root, Argon tells him that he is no longer alone.

“This is the root of your life, the root of your family. You are bound to this land and to this family. Plant it. It will grow.”

Just as Paul finds a family through his connection with the grapevine and discovers life through nature, we are all connected to each other in some form. This form is a complex, scale-free network, created through competition, cooperation, meetings, and farewells, always forming a different network but never completely unrelated. Even within chaos and change, certain rules and principles exist.

When we look at nature, it may seem like the law of the jungle prevails. Without hunting, survival is impossible, and the competition for food is equally fierce. Additionally, without protecting oneself from other predators, survival is not guaranteed. The logic of survival of the fittest and the struggle for existence seem to govern all of nature. However, upon closer observation, we see that cooperation, collaboration, and coexistence are also present. While it is known that even in the animal kingdom, antisocial behavior is disciplined, reconciliation can also be found in the jungle. Although animals compete for food and mates, they do not always engage in competition. A closer look at the animal world reveals that relationships based on mutual help are more common. Small animals often move in groups, appearing larger and more intimidating to predators, which reduces their chances of being preyed upon. Hyenas are smaller and weaker than lions, but their strength in numbers and cohesion allows them to maintain a balance of power. Many animals engage in cooperative behaviors, such as grooming each other. Examples include vampire bats sharing food and many birds, like penguins in Antarctica, taking care of other birds’ chicks for the benefit of the group. Jane Goodall, an ethologist, has frequently observed chimpanzee groups in Tanzania adopting orphaned baby chimpanzees.

Whether such mutual dependence and behaviors among animals in nature are driven by genetic instincts or situational judgment is unclear, but what is certain is that they benefit one another. Humans are also inherently selfish. The world we live in demands competition as fierce as that in the jungle. Our daily lives seem to consist of activities driven by selfish desires. Richard Dawkins, the author of The Selfish Gene, argues that humans are merely machines created to preserve genes. He claims that it is not we who are selfish, but our genes. The purpose of these genes is to replicate themselves as much as possible and to preserve themselves for as long as possible. Our existence is controlled by our genes. The smallest unit of life is the cell, and our bodies are made up of cells. However, it is not the cells themselves, not even the chromosomes within the cell nucleus, nor the DNA that makes up the chromosomes, but about 30,000 of the 3 billion bases that constitute DNA that control us like puppets. In fact, this hypothesis of the selfish gene can plausibly explain much of human behavior.

The love of a mother who sacrifices her life for her child in danger and the dedication and love for family can be interpreted as selfish behaviors aimed at preserving genes in organisms that share similar genes. As previously mentioned, men’s tendencies to have many affairs may be a natural phenomenon aimed at replicating their selfish genes as much as possible. Richard Dawkins explains in his book The Selfish Gene, “In any male or female individual, maximizing the total reproductive success during their lifetime is desired. Due to fundamental differences in the size and number of sperm and eggs, males generally tend to exhibit promiscuity and a lack of offspring care. In response, females have developed two main strategies: choosing a masculine male or prioritizing a male who will ensure the happiness of the family.” This is not much different from what David Buss discusses in The Evolution of Desire. However, Dawkins goes further to interpret humans as beings who eat, work, and love according to the will of their genes for the purpose of gene replication.

There is some truth to this. However, the selfish gene theory cannot explain everything in the world. For example, there are many devoted sons and daughters in the world, particularly in Eastern cultures where examples of filial piety abound. The children have already received all their “selfish genes” from their parents. Despite having no way to increase the replication of their genes by looking back, they are moved to tears by the word “mother” and feel reverence for the word “father.” Such phenomena are difficult to explain through the selfish gene theory. Moreover, the contents of The Selfish Gene are not the results of Richard Dawkins’ research but rather a synthesis of the achievements and theories of many evolutionary biologists. The phrase “Humans are blindly programmed robots created to preserve genes” is just a rephrasing of Edward Wilson’s 1978 book On Human Nature, which states, “A chicken is just an egg’s way of making more eggs.” While such ideas are a form of creation, Dawkins’ assertions cannot be considered a verified theory.

Nevertheless, it is undeniable that the selfish aspects of living beings, including humans, have been observed from various perspectives. On the other hand, cooperation also undeniably exists. Evolutionists explain that this cooperation itself originates from selfish motives. In other words, even altruistic behavior stems from selfish calculations. Anthropologists explain that humans developed a sense of cooperation because it was disadvantageous for survival not to help each other when hunting or farming.

Sociologists have also claimed that helping and cooperating are products of social necessity. Matt Ridley, the author of The Origins of Virtue, which seems to have been written to critique The Selfish Gene, also finds human cooperation rooted in selfish reciprocity. Ridley gives an example of our bodies: If we closely examine our body’s genes, we can see that the genes observe their own interests through cooperation. By helping each other, they form chromosomes, create cells, and produce various substances necessary for life functions, which is essential for our survival. This can also be explained without much complexity through the fable about the fight among the body parts that we heard as children. The hands, feet, and eyes all complained that the mouth was the only one having fun, eating delicious food alone. To punish the mouth, the hands and feet stopped working. The whole body became weak. In the end, the story shows that cooperation is necessary for survival.

Although I do not fully understand genes, one thing is clear: cooperation and collaboration are more beneficial than competition. Our bodies consist of tens of trillions of cells, but all the cells in one person share the same DNA. We live in a society where DNA tests are commonly used to verify facts in criminal cases or confirm family relationships. This DNA, regardless of which part of the body it is taken from, remains the same. While all the cells share the same DNA, only the genes with their switches turned on are expressed, forming different cells and functioning differently. Without the cooperation of all these cells, we cannot survive. Perhaps this is because they all share the same DNA—the DNA that contains those selfish genes.

Cooperation and collaboration are necessary not only for survival but also to achieve better results. Consider the case of teamwork, which makes this clear. One method of collaboration is the division of labor. Simply put, collaboration means working together, and division of labor means splitting the work. Even when the division of labor is simple and unrelated to individual skills or abilities, it can lead to significant increases in productivity. In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith uses the example of a pin factory to explain the benefits of division of labor. By dividing the pin-making process into various stages and having each worker specialize in their respective area, ten workers can produce approximately 48,000 pins a day, whereas a single worker performing all tasks alone could not produce even 20. In this case, the increase in productivity through division of labor is 240-fold. Where does such an enormous increase in productivity come from? Fundamentally, it comes from the saving of time, as there is less time wasted moving from one task to another. Moreover, as workers become more skilled in their specific tasks, productivity increases further. Now, consider if each person does what they are best at. Clearly, based on individual personalities, some tasks are better suited to certain people. Some individuals are skilled in delicate work, others are physically stronger, and still, others excel in singing or designing. It seems evident that productivity can be increased through collaboration. When we add the enjoyment of working together, cooperation becomes an indispensable way of life in human society. Historically, societies that have been well-organized and cooperative have dominated those that were not, both socially, culturally, economically, and militarily.

The problem lies in the fact that some of us, with our selfish genes, break such social agreements. The solution to this issue can be found in institutions and culture. When selfish behavior becomes rampant, enforcement becomes stronger, and as new forms of selfish betrayal emerge, society has progressed by reinforcing these enforcements, albeit at a social cost. A concept that many are familiar with from game theory is the “prisoner’s dilemma.” This is a situation where two suspects would benefit from cooperating but, due to their selfish decisions, end up with a worse outcome. The prisoner’s dilemma game begins like this: Two co-conspirators are held in separate, isolated spaces where they cannot communicate and are given a choice—confess or deny. If both deny, they each receive one year in prison. If both confess, they each get five years. Hence, choosing denial is more desirable than confession. However, if one denies and the other confesses, the one who denies takes all the blame and receives a 20-year sentence, while the confessor is released. What is the best choice for each individual? The best choice for each is to confess. By considering the possible actions of the other, one can see that if the other denies, confessing will result in release. If the other confesses, confessing will avoid taking all the blame. Thus, despite the fact that mutual denial would result in a lighter sentence of one year each, both choose to confess and end up with five years each due to their rational, selfish decisions.

But what if the prisoner’s dilemma is not a one-time game, but repeated? If each game is considered the last, the result will be the same as a single-instance prisoner’s dilemma. However, changing the rules slightly can make cooperation the superior strategy. For example, imagine a more realistic situation where the punishment is not severe. Two prisoners are in a cell with a window so high that they can only escape by cooperating. If one stands on the other’s shoulders and is pulled up, both can escape. The problem arises if the first prisoner, after reaching the window, breaks the agreement and escapes alone. The first prisoner benefits from not wasting time helping the other, but the second prisoner, left behind, faces the worst situation. In reality, depending on the likelihood of getting caught and the severity of the punishment, different choices might be made. If the guard hasn’t noticed, the first prisoner might still help the second, holding onto the agreement.

Robert Axelrod, a political scientist at the University of Michigan, explains that when the prisoner’s dilemma game is repeated, cooperation becomes possible, using an example from World War I on the Western Front. As German and British troops dug trenches and faced each other, they eventually began merely pretending to shoot, even observing a truce during mealtimes. Real shooting, aiming to kill, would have resulted in mutual loss.

The issue is that human selfishness does not always lead to cooperation, which incurs many social costs. Why do many betray, even though cooperation is more beneficial for selfish genes and selfish humans? The selfish gene aims to replicate itself more and preserve itself for longer. To ensure its longevity, it needs to create a better future environment. However, some genes are fixated on immediate gains, as if they possess “foolish genes.” Because of such genes, society has to bear greater costs.

Education aimed at fostering morality, legal enforcement, and similar measures are the costs we all must bear together. Even animals punish those who betray their society. For example, it is known that selfish individuals in chimpanzee societies are punished, sometimes through lynching. When humans lived in smaller communities, this might not have been a big problem since the village elders could punish the betrayers. However, as larger communities formed, it became difficult to enforce such rules by the elders alone. To prevent people from taking what belongs to others or causing harm, humans had to rely on religion, morality, and law. Human society likely understood the need and importance of cooperation early on.

All religions pursue the “good” that comes from cooperation. By 2000 B.C., the Sumerians already had the Code of Ur-Nammu, the Babylonians had the Code of Hammurabi, the Jews had the Ten Commandments, and Korea had the Eight Prohibitions during the Gojoseon period. All these laws included punishments for those who did not cooperate, such as theft or injury. One characteristic of ancient law was the Lex Talionis, or the law of retribution—“an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.”

The difference between advanced and underdeveloped countries can be attributed to the degree of cooperation. A society’s level of cooperation can be measured by its order and trust. Indeed, societies where cooperation is easier tend to be more economically developed. Since social costs are reduced, this is perhaps an expected outcome. Does this mean that people in developed countries are more altruistic? Not necessarily. Today’s cooperation may be the result of social costs paid earlier. There might have been more social betrayers, which could have necessitated stricter and more stringent laws. In this sense, we have produced many lawyers thanks to the “foolish gene” that pursues short-term, immediate gains. While we all share the cost, it is a societal issue. What should we do on an individual level?

On a personal level, we implement various strategies to guard against potential betrayers. For example, humans strive to learn the skill of reading others’ intentions. Some psychologists explain that our inductive reasoning abilities developed to detect others’ deceit. We form hypotheses about others, observe their actions, and continually test these hypotheses. From such experiences, we develop the ability to form new hypotheses about others and test them, leading to the development of inductive reasoning. This is how we learn to read people. This is not much different from what we’ve discussed so far. As Eric Beinhocker introduces in The Origin of Wealth, Axelrod examines this issue through the prisoner’s dilemma game. Instead of mathematical analysis, he has participants engage directly in a tournament-style prisoner’s dilemma game, where multiple games are played, and the overall score determines the winner. This version of the game is closer to real life. The results revealed that the most successful strategy was the ancient Lex Talionis, “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” This strategy is known as “tit-for-tat.” While the dictionary meaning of tit-for-tat is “to give as good as one gets,” its strategic elements include being gentlemanly at first, but immediately and firmly retaliating if betrayed. The strategy involves cooperating unconditionally with someone upon first meeting them but then mimicking their subsequent decisions. If they do not betray, neither do you. However, if they do, you retaliate with betrayal, which is the best strategy. Seeing how similar this is to the ancient law of retribution, it appears that humans may have always understood their nature.

British professors Gilbert Roberts and Thomas Sherratt introduced research results in the scientific weekly Nature (July 9, 1998), stating that “cooperation among animals comes from accumulated investment.” According to them, cooperation becomes a kind of investment to earn the cooperation and trust of others and to prevent potential betrayal. They mention that puffins use their beaks to preen each other’s wings. Through such simple cooperation, trust is built up, leading them to eventually share food. Roberts and Sherratt went further and conducted a simulation comparing various cooperative strategies by setting betrayal to zero and scoring based on the degree of cooperation. Their research concluded that the “raise-the-stakes” strategy was the most effective. This strategy involves initially matching the level of cooperation to that of the other party or slightly more to prevent betrayal, but gradually increasing the level of cooperation. As this process repeats and trust and cooperation build, higher levels of cooperation can be achieved.

Humans are the same. When meeting someone for the first time, we start with a probing phase before deciding on the level of cooperation. In a one-time prisoner’s dilemma game, betrayal is the superior strategy, but in a repeated game, cooperation can lead to better outcomes. Trust in human relationships ultimately depends on how repetitive and sustained the interactions are.

Adam Smith points out that “the larger the scale of business and the more frequent the transactions, the greater the incentive to act honestly to protect one’s reputation.” Consider how the most successful merchants, such as the Chinese diaspora and Jewish people, value trust as highly as their lives and pass it down through generations. This not only teaches the importance of maintaining trust for cooperation but also suggests that it is difficult to achieve. We all have trust accounts, similar to Stephen Covey’s emotional bank accounts. This means that we must build trust by depositing assets of trust into each other’s accounts and managing those accounts accordingly. We should settle or be cautious with those whose trust accounts have gone negative. Meanwhile, to gain the cooperation of others, we must continue to build up our credit balance in the trust account with them. Cooperation is a better way for mutual benefit. We can call this kind of cooperative relationship reciprocal altruism.

People tend not to think positively about selfishness. However, we cannot deny that we are all selfish. Moreover, selfishness is not always negative. Selfishness provides us with the motivation to work. Denying human selfishness can be a difficult choice because there will always be people with “foolish genes.” While cooperation and working together is an ideal way of life, being deceived or betrayed comes with enormous costs and suffering. It’s a world where you can’t trust people carelessly, but neither can you avoid trusting them altogether. Beyond cooperating with others, we must learn the judgment to avoid being deceived by “foolish genes.” While it is advisable to avoid encounters with them when possible, discerning and responding to those with foolish genes by effectively employing tit-for-tat strategies and managing trust accounts is crucial wisdom.

“To know one’s self is wisdom, but to know one’s neighbor is genius.” ~ Minna Antrim

답글 남기기