Let sentences connect!

Go to Koren Version

Explore the Table of Contents

Normally, “context” refers to the sentence’s surrounding conditions or background. However, in English, “context” has a broader meaning that includes the rhythm and intensity of the voice delivering the words, facial expressions, gestures, and even the surrounding situation during the speech. It implies that the content of a movie is not solely composed of the actors’ lines (text). Therefore, it’s not just the text but everything coming together (co, con, com, cor, col) that forms the context included in the content.

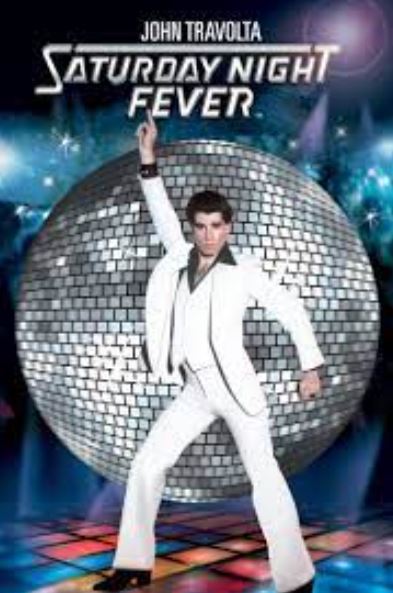

In the late 70s, the important context of movies like “Saturday Night Fever” (1977), “Flashdance” (1983), “Footloose” (1984), and “Dirty Dancing” (1987) was more about the music than the dialogue. For example, “Saturday Night Fever” featured the Bee Gees’ “Stayin’ Alive”, a band as popular as the Beatles at the time.

This doesn’t mean that these beloved movies lacked memorable lines. One notable quote is from Frank Manero Jr. to his brother Tony, who had aspirations of becoming a priest:

Frank Manero Jr.: “Tony, the only way you’re gonna survive is to do what you think is right, not what they keep trying to jam you into. You let ’em do that and you’re gonna end up in nothing but misery!”

Combining sentences into a single structure is similar to how we compile lists of words. When one sentence is integrated into another, it becomes what we call a “clause.” Despite this transformation, its function within the overall sentence doesn’t change; it acts just like any word or phrase would. Using conjunctions such as “and,” “but,” or “or,” we can link these clauses or use them as nouns, adjectives, or adverbs. The key is that, within a sentence, each element—whether a word, phrase, or clause—must serve its intended purpose. Even in complex sentences, the basic structure remains consistent:

S+V + (who+what) + [where+why+how+when]

S+V + (Noun+Noun) + [Adverb+Adverb+Adverb+Adverb+Adverb]

When a clause becomes a component of a sentence, instead of being called a noun, adjective, or adverb, it’s referred to as a noun clause, adjective clause, or adverbial clause. You can also think of these as longer forms of nouns, adjectives, and adverbs. No matter if it’s just one word or a group of words, its job in the sentence doesn’t change. It still functions as a noun, an adjective, or an adverb, even if it’s longer.

Noun Clause

The simplest way to create a noun clause is by adding ‘that’ in front of it. Recall the following line by Richard ‘Rick’ Blaine, the owner of a cafe in Casablanca:

Richard ‘Rick’ Blaine:: “Louis, I think (that) this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.” (CASABLANCA: 1942)

In this line, “I think” is a transitive verb. Therefore, an object must follow ‘think’. To become an object, nouns or things disguised as nouns must appear, and that’s where conjunctions like ‘that’ are needed. However, in conversational language, ‘that’ is often omitted, so the entire phrase following ‘think’ must be recognized as a noun clause. Or, as per our defined principle of English, it’s also acceptable to think of it as adding a long explanation to resolve the natural curiosity of ‘what’ that follows the subject and verb “I think”. Another example:

VERBAL KINT: “The greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was convincing the world (that) he didn’t exist.” (THE USUAL SUSPECTS, Columbia, 1995)

Conjunctions like ‘if’ and ‘whether’, besides ‘that’, are used to turn a sentence into a noun.

Forrest Gump: “Jenny, I don’t know if Momma was right or if, if it’s Lieutenant Dan. I don’t know if we each have a destiny, or if we’re all just floating around accidental-like on a breeze.” (FORREST GUMP)

“If” was used as an object with the meaning of “whether or not.” Schools teach that there are five ways or types of noun clauses. If words like relative pronouns or complex feel complicated, just think of clauses led by that, if, whether, and question words.

| conjunctions | that |

| whether, if. | whether, if |

| Interrogative clauses | who, where, why, how, where |

| relative pronoun | what |

| complex relative pronouns | whoever, whatever, whichever |

Captain: “What we’ve got here is failure to communicate.” (COOL HAND LUKE, 1967)

“What we’ve got here” functions as a noun clause serving the role of the subject. It leads the noun clause, so it can naturally also serve as the object.

The following quote is from “When Harry Met Sally” where an older woman orders the same food as Sally after she makes a loud, playful noise in a restaurant. “What she’s having” acts as a noun, fulfilling the role of ‘what’ in One Pattern English Sentence Structure.

Older Woman Customer: [to waiter] “I’ll have what she’s having.” (WHEN HARRY MET SALLY: 1989)

Let’s look at examples where noun clauses led by “what” can serve as both the subject and the complement.

God: “People want me to do everything for them. What they don’t realize is that they have the power. You want to see a miracle? Be the miracle.” (Bruce Almighty)

Wizard: “Look at it this way. A man takes a job, you know? And that job – I mean, like that – That becomes what he is.” (TAXI DRIVER)

As summarized above, question words can create noun clauses that act as both subjects and objects. The movie Forrest Gump begins with the protagonist remembering his mother’s words.

Forrest Gump: “My momma always said you can tell a lot about a person by their shoes, where they go, where they’ve been. I’ve worn lots of shoes, I bet if I think about it real hard I can remember my first pair of shoes.” (FORREST GUMP)

what you think is right & how to

The phrase “Do what you think is right” simply means “Do what is right.” To add the meaning ‘what you think,’ you can insert ‘you think’ (or other verbs related to thinking). In English grammar, this expression is called an indirect question. If turned into a question, it becomes “What do you think is right?”

Frank Manero Jr.:Tony, the only way you’re gonna survive is to do what you think is right, not what they keep trying to jam you into. <Saturday Night Fever, 1977>

Noun clauses including a questioning word can be condensed into [questioning word + to infinitive]. Thus, when a questioning word precedes ‘to’ in an infinitive form, it necessarily takes on a noun usage meaning ‘the act of doing what the questioning word specifies.’

MARIE ‘SLIM’ BROWNING: “You know how to whistle, don’t you, Steve? You just put your lips together and blow.” (TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT: 1944)

AJ: “Harry’ll do it. I know it. He doesn’t know how to fail.” (Armageddon, 1998)

답글 남기기