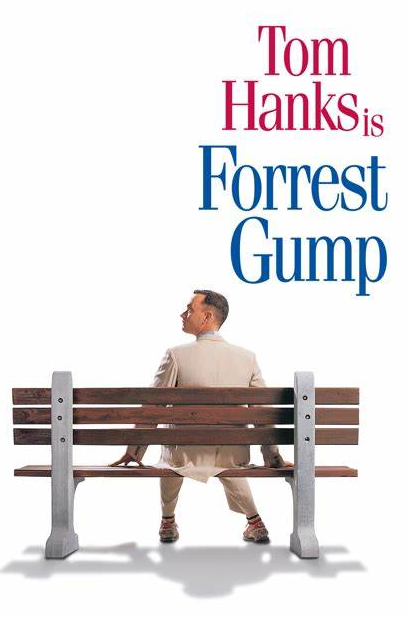

In the 1994 film “Forrest Gump,” starring Tom Hanks, the protagonist, Forrest Gump, has an IQ of 75 and suffers from a leg disability. Despite these challenges, Forrest discovers his talent for running, which leads him to graduate high school as a football player and enter college on a football scholarship. As a young adult, he joins the army, earns a medal for saving his comrades with his running skills, and becomes wealthy by shrimp fishing after his discharge. Although he reunites with his first love, Jenny, she leaves him again. In his disappointment, Forrest embarks on a three-year running journey across the country, becoming an American hero. Forrest lives a simple life, never overthinking anything. He followed his mother’s advice as a child, loved only one woman as he grew, and succeeded by simply running and thinking straightforwardly. What about us, with IQs exceeding 75?

I once saw the slogan “Think as You Live!” on the chalkboard of a small logistics company, created because employees often forgot their tasks. IBM’s motto is also ‘Think.’ Their ten guiding principles all revolve around this concept. IBM’s website still has a dedicated ‘Think’ section, and they even named their laptops ‘ThinkPads.’ Conversely, our society emphasizes reading so much that it may neglect the importance of thinking. Reading should be a dialogue with the author, involving deep thought, where the true value of reading lies. This is why Joe, the protagonist of “Idiocracy,” stresses not just reading but also thinking.

Words like thought, reason, mind, and spirit all refer to the brain’s activities, though their meanings differ slightly. ‘Thought’ often means the activity of remembering and judging, requiring logical reasoning such as deductive and inductive reasoning. Through thought, we decide, choose, and create. Human thinking seems limitless, evidenced by our creations: airplanes, satellites, and wireless phones. However, numerically, our thinking ability isn’t so impressive.

Compared to our massive memory capacity, our brain’s thinking ability isn’t remarkable. Our computational ability is especially lacking. Computers have central processing units (CPUs) for executing commands by retrieving information from hard drives. Similarly, humans retrieve information from long-term memory for thought. Today’s PCs operate at over 1 GHz, while human thinking speed is about 10 MHz, making PCs at least 100 times faster. This speed difference makes it difficult for us to compete. Humans also show inferior information processing capabilities compared to even the most basic computers when making decisions involving multiple elements, often making calculation errors.

Computation, a form of deductive reasoning, involves finding specific solutions based on general principles, following predetermined rules. Computers perform such computations using ‘if-then-else’ logic. Despite their simplicity, computers achieve remarkable computational feats due to their speed. Conversely, humans excel with slower thinking skills compared to computers.

In economics, humans are considered rational, meaning they align their actions with their interests, maximizing benefits and minimizing costs without mistakes. Perfectly rational humans analyze their environment thoroughly to maximize their benefits. For instance, consumer theory derives demand functions through utility maximization, while producer theory derives supply functions through profit maximization, with the law of supply and demand emerging from these functions.

Even assuming perfect rationality, our economic theories can describe reality well if irrational actions are outweighed by rational ones in a large market. Irrational people are inevitably exploited by those making rational decisions.

Game theory, a branch of economics, also relies on human rationality. All games in game theory assume mutual knowledge of each other’s rationality, focusing on logical strategies without deception, threats, or persuasion. The ‘rational expectations hypothesis,’ proposed by Robert Lucas in the 1970s, further assumes humans rationally predict the future using all available information, suggesting government economic policies are ineffective since their outcomes are anticipated and preemptively acted upon. The efficiency of capital markets also stems from this hypothesis, making it difficult to achieve returns beyond market rates.

Though everyone attempts to predict the future, the reality doesn’t match the hypothesis’s level of rationality. Access to information is unequal, and even with information, not everyone can use it effectively in decision-making. This is why financial institutions invest heavily in gathering and analyzing information, employing highly paid financial experts.

While not perfectly rational, people generally make the best choices within their given situations, despite their limitations, errors, and time constraints. Though we cannot be perfectly rational, we aim for rationality, possibly achieving sophisticated or clever rationality considering irrational factors.

So, why do humans struggle with even a few variables? It’s due to speed and capacity. For computers to function optimally, the CPU and RAM speeds must balance. A high-performing CPU alone doesn’t enhance speed without corresponding RAM capacity and transfer speed. Similarly, human short-term memory, typically limited to seven chunks of information, hampers our slow thinking speed. Thus, the first hindrance to human rationality is our slow thinking speed and limited memory capacity.

Other factors also impede our rationality. The most ironic and significant is our accumulated knowledge and information, built through learning and experience, which influences how we interpret new information. Prejudices, biases, and anchoring—psychological tendencies to interpret new information based on past experiences or knowledge—affect our rational decisions. For example, the clothing brand FCUK (French Connection United Kingdom) may initially evoke an English expletive, illustrating how we interpret new information using familiar words or sentences.

Our ability to quickly process documents relies on recognizing familiar expressions rather than reading each word or letter. Mistakes arise as a trade-off for delegating many tasks to our subconscious for efficiency.

This interference appears not only in sentences or situations but also in value judgments and decision-making stages, often stemming from human psychology and emotions. Some psychologists claim emotions influence over 90% of our decisions, indicating that despite our rational aspirations, we may act irrationally under emotional influence.

In the Ultimatum Game, a thought experiment illustrates this. If offered 5 million won to share, where one party proposes an uneven split (e.g., 4,999,000 won to them, 1,000 won to you), the rational choice would be to accept any positive amount. However, emotional dissatisfaction typically leads to rejecting such unfair proposals, demonstrating how emotions override rationality.

Other human traits also impede rational judgment, such as our tendency to think favorably of ourselves, focus more on risks than benefits, and conform to others’ actions or opinions. These traits, alongside cultural influences, affect our decisions, sometimes leading to irrational outcomes. Human rationality faces limitations due to our thinking speed, capacity, and other factors like emotional and psychological influences.

Given these challenges, how can we find satisfactory and superior solutions? By simplifying and breaking problems into manageable steps. Even complex problems can be addressed incrementally with enough time and resources. For national decisions, numerous participants can contribute, with specialized research institutions and government departments handling their respective areas. Supercomputers can also assist with calculations, integrating results for decision-making.

In daily life, to overcome our thinking limitations, we should narrow our thinking scope, focus on one problem at a time, and discard or abandon unnecessary aspects. Our computers slow down with unnecessary programs, icons, and hidden malware, similar to how our thoughts get cluttered. Concentrating on one feature or variable at a time, breaking problems into manageable steps, helps avoid errors and saves time.

In moments requiring important decisions, we must divide our thoughts and decide what to discard or abandon. While it would be ideal to consider everything, reality often demands prioritization and simplification. John Maeda, the author of “The Laws of Simplicity,” defines simplicity as removing the obvious and adding the meaningful.

Simplicity is about subtracting the obvious, and adding the meaningful.

Given limited time, focusing on key aspects is crucial. With some time, we can use a two-by-two matrix to analyze opposing elements, like strengths and weaknesses, costs and benefits, or short-term and long-term perspectives. For instance, understanding human nature by listing evidence of both good and evil sides helps form a hypothesis, though not an absolute proof.

A 2×2 matrix approach helps handle complex situations by breaking them into manageable parts.

Eisenhower’s principle, based on urgency and importance, exemplifies this method, requiring skill and creativity to apply effectively.

Simplification requires effort and practice, a necessary skill for expressing ourselves to others who, like us, think quickly but struggle with complexity. Many standardized matrices have evolved as presentation techniques to overcome our thinking limitations, reducing scope and focusing on key features.

Our brain possesses blessed abilities beyond what computers can achieve, offering ways to simplify and make superior decisions despite our limitations.

답글 남기기