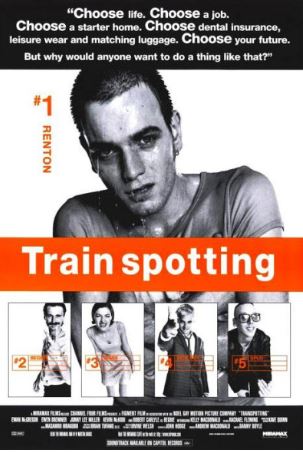

The title of the 1996 British film Trainspotting literally means counting or recording the numbers of trains as they arrive at the station. Surprisingly, many British people spend their time on this purposeless activity, similar to how anglers pass the time fishing. The film Trainspotting depicts young people who, unable to cope with a world full of uncertainties, turn to drugs and lead idle lives. The movie begins with a scene where the protagonist, Mark Renton (Ewan McGregor), is being chased by what appears to be the police, accompanied by a voiceover stating, “Choose life. Choose a job. Choose a career. Choose a family.” However, Renton immediately declares his decision to take a different path:

“Why would I want to do a thing like that? I chose not to choose life.”

Choosing not to choose can also be a viable option. Not making a choice expresses the intention to accept the current situation or to wait for a better choice. After long deliberation, it is sometimes better to delay making a decision than to make a wrong choice. This is because we often fall into the “pitfalls of choice.”

Economics and decision-making theories provide us with simple yet useful frameworks for making choices. Marginal analysis and cost-benefit analysis, if we can accurately assess costs and benefits, allow us to make rational decisions. The problem is that costs and benefits are often not so clear-cut. Many costs and benefits cannot be expressed in exact numbers. For various reasons, the world does not provide us with definitive answers, leaving us to rely on subjective judgment and intuitive evaluation.

In this process, we sometimes make errors in our choices due to misconceptions. The most common mistakes are related to the variable of time. For example, if costs and benefits occur only once, the decision-making process might be somewhat straightforward. However, most of life’s decisions involve multiple costs and various benefits that do not occur simultaneously. A decision made today may require ongoing effort and continuous costs in the future. Conversely, the benefits may not materialize until far into the future. In such cases, we are prone to focusing on immediate benefits. Of course, 1 million won today and 1 million won in 10 years have entirely different values. If given a choice, anyone would choose the 1 million won available today. However, if it were 2 million won in 10 years, we would need to reconsider. This is where the concept of discount rates in economics comes into play. The discount rate represents the present value of expected future benefits. If the expected benefit is 10%, then 2 million won in 10 years is worth less than 1 million won today. However, if it were 10 million won in 10 years, the situation changes. The value obtained from good habits or learning surpasses such numbers because it generates not only 10 million won in 10 years but also continues to provide ongoing income thereafter. This is why becoming wealthy involves not just earning money through hard work but also creating income-generating structures. Nonetheless, we often make the mistake of overemphasizing short-term gains. This “time trap” is a common occurrence.

At one time in the United States, Coca-Cola and Pepsi engaged in a taste test war known as the “Pepsi Challenge” in the 1970s. This blind taste test had participants sample Coca-Cola and Pepsi with their eyes closed and then choose. Pepsi, being sweeter than Coca-Cola, often came out on top in these initial taste tests. The continuous stream of Pepsi’s victories in TV commercials made Coca-Cola’s executives anxious. Ultimately, Coca-Cola’s executives made the historic mistake of adding caramel flavor to increase the sweetness of Coca-Cola. However, this was a poor choice that fell into the time trap. While participants in taste tests took just one sip, real-life consumers drank an entire glass or can. Consumers do not choose cola based on a single sip’s sweetness but on the sustained refreshment and thrill throughout the entire drink. Coca-Cola realized it was a wrong choice after losing a significant market share. We too often make similar momentary choices based on misconceptions.

For wise decisions, all benefits and costs must be considered together, but when there are time and spatial differences in their occurrence, one side may be overlooked. This happens when we focus on benefits and forget the necessary costs. There was once excitement over the invention of a water-powered car. A demonstration was held with many people and the media present. When the car successfully ran on water instead of gasoline, everyone cheered, thinking of the environmental benefits and economic impact. However, it was later revealed that the cost of converting water into fuel far exceeded that of using gasoline. The optimistic nature of people, combined with herd mentality, led them to ignore the obvious cost aspects.

There are “pitfalls of choice” everywhere because we often miss costs that must be considered or mistakenly think of costs that shouldn’t be considered as actual costs. Economics has formalized these important concepts as sunk costs and opportunity costs. To make rational choices, we need to assess not only what constitutes a benefit but also what constitutes a cost. Among these costs, one of the most famous and yet often overlooked because they are not directly visible or actually paid is opportunity cost. Opportunity cost refers to the total value of what is forgone by choosing one option over another. In other words, it is the benefit one could have received but gave up by not choosing the alternative. Choosing one thing means giving up other potential opportunities, and the most valuable among these forgone opportunities is the opportunity cost. Whether consciously or unconsciously, we base our decisions on opportunity cost, often falling into traps as a result.

Let’s consider a situation where we go to the movies with friends. Suppose the ticket costs 8,000 won. What is the total cost we incur? Is the ticket price of 8,000 won the only cost? No, it is not. The cost we pay to watch the movie includes not only the monetary cost but also the time cost. Suppose it takes 4 hours in total, including travel time to and from the theater and the duration of the movie. Naturally, opportunity costs vary from person to person. For instance, if someone earns 100,000 won per hour, their opportunity cost for choosing to watch a movie amounts to 400,000 won, assuming they could have worked during that time. Why, then, would they choose such an expensive movie? It’s because the perceived benefits outweigh the costs. Alternatively, it could be because there is no opportunity to work during that time, making the benefit of watching the movie greater than the opportunity cost of reading a book or engaging in other activities. In essence, choices inherently consider opportunity costs, whether we realize it or not. If one forgoes significant beneficial activities to watch a movie, it can be seen as falling into an irrational “pitfall of choice.” If one’s mind is uneasy, it is a sign that they are incurring an opportunity cost.

A more crucial aspect related to costs is understanding “what is not a cost.” This is because we often mistakenly consider something that isn’t a marginal cost as a cost. This misinterpreted cost is known as sunk cost. Sunk costs are expenses that have already been incurred and cannot affect current decision-making. They should not influence current decisions. The stubbornness of continuing promotions and advertisements for a product launched after significant investment, or the folly of continuing strenuous exercise at an expensive sports club membership despite arm strain, stems from an obsession with sunk costs. Costs already incurred to develop a new car have no bearing on marketing decisions. These expenses do not influence future sales of the car. What matters is the potential earnings from the car moving forward. Consider this scenario: you booked a hotel in Jeju for 100,000 won and paid a 20,000 won deposit. If you don’t go on the designated date, the 20,000 won deposit is non-refundable. Now, suppose you get an offer to stay at a better hotel for 80,000 won. Which hotel should you choose? Many might cling to the original booking to avoid wasting the 20,000 won deposit, even though the decision should be between paying 80,000 won for a better hotel or paying 80,000 won for the originally booked hotel.

Here’s another clear example. Suppose you value watching a newly released movie at 10,000 won, but you lost a pre-purchased ticket worth 6,000 won. Should you buy another ticket or decide against watching the movie because it would mean spending 12,000 won in total? A rational decision-maker would buy another ticket because the marginal cost is 6,000 won, while the marginal benefit is 10,000 won. The 6,000 won for the lost ticket is already a sunk cost. It’s like crying over spilled milk; it doesn’t change anything.

The more we invest in something, the more responsibility we feel towards it. Long negotiations or projects are often deemed important regardless of the benefits they yield. Investments don’t necessarily have to be monetary. It’s difficult to abandon a tedious and unhelpful book halfway through, even though it would be wiser to read another book in that time. The same applies to unhealthy relationships. Even if they are not beneficial, severing ties is not easy. It seems no one is free from the sunk cost fallacy. The same goes for corporate investments. Despite a project being proven unprofitable, companies often continue due to the money and effort already spent. This trap ensnares not only intelligent individuals but also organizations with numerous experts. They fail to acknowledge the trap due to issues of accountability and, instead, rationalize or hope the situation might improve, listening to optimistic opinions from others. However, sunk costs can never be recovered, and prolonging them only increases losses. To avoid the sunk cost fallacy in decision-making, it’s crucial to remember that the past is the past, and spent money is spent money.

Besides opportunity and sunk costs, there are costs that are not easily visible. The simple principle of comparing benefits and costs to choose the option with greater benefits becomes useless if hidden costs are not identified. For example, in a new national development project, the benefits are relatively easy to identify, but the negative environmental impacts, or costs, are less visible. Additionally, human nature tends to interpret problems positively, leading to an overemphasis on benefits and underestimation of costs.

Due to limitations in thinking speed and capacity, we sometimes make wrong decisions. Economics assumes that we are all highly rational individuals.

However, even if we are rational, we cannot always identify all hidden benefits and costs, resulting in suboptimal choices. Moreover, in reality, we are often overly confident or influenced by emotions or unconscious factors, leading to irrational choices. These are referred to as “psychological traps.” They stem from the inherent limitations of human thinking. Although numerous psychological traits of humans are reported, those related to choice can be summarized into a few key points. Firstly, as previously mentioned, there is a tendency to interpret phenomena based on one’s own experiences and knowledge, often referred to as stereotypes. Our consciousness delegates many tasks to the unconscious for efficiency. Secondly, there is a tendency to accept the movements or opinions of the group one belongs to as desirable, sometimes beyond rational levels. This might be a means of avoiding risks or an instinctive social behavior. Thirdly, to avoid risks, people instinctively perceive negative aspects more strongly than they actually are. This might be because, historically, a single risky situation could determine survival. Fourthly, there is a tendency to interpret situations positively once they affect us or we make decisions, resisting admitting mistakes and holding expectations of positive outcomes even in low-probability scenarios. These four human characteristics are helpful for an efficient daily life but can lead to falling into the “pitfalls of choice” if not recognized.

The trap of stereotypes involves seeing what we want to see and believing what we want to believe. The status quo bias, a type of stereotype trap, occurs due to a conservative inclination to maintain the current state during decision-making, focusing on options that support the status quo. Like the young people in Trainspotting, this involves rationalizing inaction. This phenomenon is due to our stronger instinct to avoid risk than to take risks, and our tendency to prioritize existing information. As explored in Knowing Oneself, our judgments are influenced by the most dramatic or recent experiences stored in our unconscious. This is how human decision-making systems have evolved. When we hold preconceived notions, we tend to accept information that supports our initial views and ignore information that contradicts them. Thus, as discussed, it is crucial to view problems from multiple perspectives and consult with others. However, problems can arise here too. If the consulted person is an expert, their influence might create new stereotypes. What we seek is a variety of perspectives, not decisions made by others.

The error of making choices based on overly strong negative information is relatively well-known. For example, Daniel McFadden, co-recipient of the 2000 Nobel Prize in Economics, reported that people tend to overestimate or underestimate the odds of winning a lottery depending on whether the explanation emphasizes gains or losses. The same story can lead to different choices depending on whether the positive aspects are highlighted first or the negative ones are. In the article “10 Ways to Make Better Decisions” published in New Scientist on May 5, 2007, Kate Douglas and Dan Jones provide the following example: Suppose a disease outbreak will result in the death of 600 people if no action is taken, and you must choose between two plans. Plan A will save 200 people. Plan B has a one-third chance of saving all 600 people and a two-thirds chance of saving none. Which plan would you choose? Statistically, the outcomes of plans A and B are equivalent, but most people instinctively consider Plan A the better option due to the negative perception of the two-thirds chance of saving none in Plan B. Douglas and Jones, like McFadden, emphasize that “in a positive frame, people avoid negative or risky situations, whereas in a negative frame, they are more willing to choose risky alternatives.” This is why food labels prefer “90% fat-free” over “10% fat,” knowing that the negative wording influences choices. Psychologists call this the negativity effect, where people give more weight to negative information than positive information.

Conversely, there is also the halo effect, which is the opposite of the negativity effect. This phenomenon occurs when one positive trait of an object or person influences the overall perception. For instance, when evaluating a person, if their appearance leaves a good impression, their intelligence or personality is also likely to be rated more positively. This tendency to view situations positively once they affect us or are our decisions can make daily life more pleasant, but if excessive, it can lead to more painful outcomes. For example, even during a stock market downturn, some might optimistically believe that only their stocks will rise. Similarly, someone who frequently criticizes others might think that the person in front of them has a good opinion of them. Without sufficient evidence, it’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking, “These people are all on my side.” Adding the arrogance of believing oneself superior to others can lead to overconfidence and self-deception, leading to falling into the pitfalls of choice. This is something we often experience and witness.

Many successful companies and entrepreneurs of the past have vanished into history due to falling into such traps. As a business becomes successful and people start recognizing and inviting them everywhere, they may unknowingly start perceiving themselves as stars. Being intoxicated by success and overestimating their abilities, they fail to recognize the seeds of failure within them. Venture companies are called such because their success rates are very low. Despite the overall low probability of success, most entrepreneurs believe they are exceptions to this rule. Furthermore, some successful entrepreneurs attribute their success entirely to their abilities. Until recently, some Korean venture founders were like this. Listed on KOSDAQ without ever having made a proper profit, their market capitalization surpassed that of traditional companies, leading them to believe their management skills and vision for the future were superior, which in turn caused difficulties for many. Let’s exclude the unethical individuals from our discussion. These people fail to recognize the ordinary fact that their success was supported by favorable environmental changes and the backing of those around them. Others can see the traps ahead, but they cannot see them for themselves.

These traps demonstrate that choices we think are always rational may not be rational at all, and therefore, the best results cannot be obtained. The best way to avoid these psychological traps is to recognize their existence. We must realize that we may not be truly objective and are prone to falling into these traps. Another factor that leads to such traps is complacency or intense emotions. Everyone has experienced making regrettable choices when influenced by strong emotions like anger or sadness. Cold reason is contrasted with passion and emotion. Losing composure makes it easy to fall into the pitfalls of choice. There is an anecdote about Genghis Khan: When he tried to drink water trickling from a rock on his way back from hunting, his hawk prevented him from drinking it. Enraged, Genghis Khan killed his beloved hawk with his sword. When he looked up again to drink the water, he saw a dead snake rotting in the pool of water. Realizing that his wise and loyal hawk had prevented him from drinking poisoned water at the cost of its life, he resolved,

“From now on, I will never make decisions when I am angry.”

답글 남기기