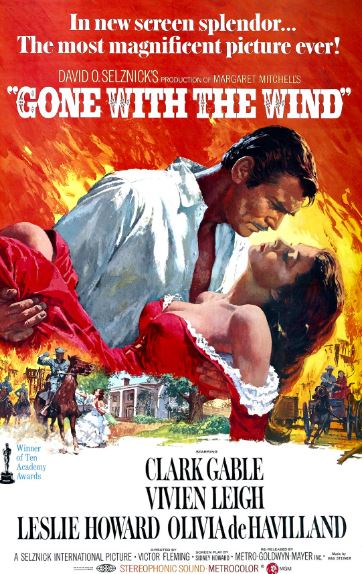

Gone with the Wind (1939), starring Vivien Leigh and Clark Gable, consistently ranks within the top 100 films in annual box office charts. Considering it has been nearly 70 years since its release, it’s often regarded as one of the greatest films ever made. One film critic even said, “There are two movies in America. One is ‘Gone with the Wind’ and the other is ‘all the rest.’” In the film’s final scene, the heroine Scarlett sends the hero Rhett away and, against the backdrop of a fiery sunset on the farm, she says,

“After all, tomorrow is another day.”

Though I have tried to view the world with simple eyes, the world is truly complex. The vast universe with 140 billion galaxies, the miraculous matter made of atoms so small that they could be cut to one hundred millionth the size of a ping-pong ball, the mystery of our bodies made of more than 60 trillion cells, and the dynamic human affairs created by over 8 billion people – this world is filled with complexities. It is perhaps natural that we cannot fully understand such a world. From the ever-expanding universe to my own self who needlessly hurt others out of anger last night, I cannot fully understand. The tumultuous story of the beautiful and passionate Scarlett leaving her third man also seems to be created beyond her own will.

Is life determined by fate or random luck? Although successful people often speak as if they had foresight about the future, in my experience, most of them were simply lucky. This is not said to demean them. Napoleon always said, “I prefer a lucky general to a good one.” In truth, those who have lived a bit know how crucial luck is. Thus, when faced with complex matters, one might simply think, “I’ll think about it tomorrow,” hoping luck will improve by then. However, lucky people have one characteristic: they constantly train and practice at least one virtue necessary for success. When such effort meets the right moment, that is luck, and it leads to success. Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States, stated, “I am a great believer in luck, and I find the harder I work, the more I have of it.”

If our life’s report card isn’t satisfactory despite our hard work, it’s too early to give up, thinking we are just unlucky. The principle of how the world works tells us that our efforts will bear fruit someday, even if it’s not everything or at the time we wanted.

As we’ve seen, the world is indeed complex and uncertain, but it is not chaos. Just as tomorrow will bring a new day’s sun, there are many inherent rules in the natural phenomena and human life we encounter. Many have tried to uncover these rules, and some have even attempted to explain the principles of our lives in just a few words. Despite many trial and error, thanks to their efforts, we now possess relatively extensive knowledge about natural phenomena and human life. All these results stem from attempts to overcome complexity. Such scholarly or philosophical endeavors can be seen as a process of simplification. By seriously examining and understanding the principles of the tangled world, or by solving difficult problems to the best of our ability, we achieve true simplicity.

This applies not only to complex disciplines or theories but also to our daily lives. What we encounter for the first time always seems complex. If you were to step into Manhattan, New York, for the first time, you would be bewildered by the complexity. But as you wander up and down, left and right, you start to find a kind of rule. Eventually, you create reference points like Central Park, and over time, the streets of Manhattan become familiar. If you understand the numbering system of the streets from a map, Manhattan quickly becomes a simple layout.

The unknown appears complex, and the known seems simple. Complexity becomes simple once understood. Learning, therefore, is a process of simplification, and most fields of study, whether natural or social sciences, work to simplify the complex world. This results in principles, rules, laws, and theories. Essentially, these are created by dissecting the complex world with a sharp knife and reassembling it with the eye of insight. Complexity can thus approach simplicity through our efforts. This is likely why Oliver Wendell Holmes, a contributor to American pragmatism, said, “For the simplicity that lies this side of complexity, I would not give a fig, but for the simplicity that lies on the other side of complexity, I would give my life.”

Most of us live ordinary lives, which means repetitive daily routines. Problems arise when sudden changes occur. It doesn’t mean there were no problems before; it’s just that we don’t recognize them as problems because we already have principles or methods to handle trivial things. For someone taking the subway for the first time, the experience itself can be a complex problem. As philosopher Karl Popper said, “All life is problem-solving.” Problems indicate a discrepancy between our current situation or phenomena and our expectations or goals, and the greater the discrepancy, the more severe the problem. Therefore, recognizing potential changes or knowing more through experience and learning makes the problems we encounter simpler and easier. However, we cannot experience or learn every problem in advance, and no problem we face is likely unique to the world. Wisdom is the ability to apply knowledge gained in one field to various problems.

True wisdom must include systematic principles for problem-solving. One of these principles is not only recognizing problems but also defining them as simply as possible and grasping their essence. Only then can we solve simple problems with a few simple principles. Recall past difficult problems; what seemed complicated may have been resolved through simple clues or failed due to missing simple steps. Blindly trusting someone or missing a single verification process can lead to failure. Conversely, discussing difficult problems with a mentor or re-examining basics to find common mistakes can lead to significant success. This applies not only to us but also to renowned problem-solvers.

This doesn’t mean all problems are easy. Rather, the simpler our principles for understanding ourselves and the world, the more likely we are to solve the problems we face. Genghis Khan, the conqueror of Asia, always valued mobility in warfare, as did Napoleon in Europe, using rapid maneuvers to collapse or paralyze the enemy’s main forces. For them, the principle of war was mobility. It wasn’t the only superior method, but because they were confident and skilled at it, it often succeeded. Of course, they also experienced failures.

While advocating for simplification to understand the world, such simplicity must include honesty in at least two aspects. First, we must acknowledge that simplified concepts are not the whole reality. Knowing that the sun rises in the east every day doesn’t mean we fully understand the sun. Completing the Human Genome Project doesn’t imply complete understanding of human genes. We have just begun to see parts of what seemed complex. Our simplification efforts may be endless in a sense. The sun rises because the earth orbits the sun, and the principle of that motion is explained by gravity. Further explanation by Einstein describes gravity as the curvature of spacetime. Simplification reveals parts of the whole, not the complete truth.

Therefore, what we gain are not perfect answers but superior solutions.

Second, if we understand a part well, we should be able to explain it simply, indicating better understanding. Physicist Richard P. Feynman is renowned for his lectures, collected in “The Feynman Lectures on Physics,” which remain essential reading for physics students worldwide. His lectures are akin to Todd Buchholz’s “New Ideas from Dead Economists” in economics. Both Feynman and Buchholz communicate the achievements of their fields in accessible language for the general public. Feynman admitted during a lecture at Caltech that if he couldn’t explain something to freshmen, it meant he didn’t understand it well himself.

“I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t reduce it to the freshman level. That means we don’t really understand it.”

In other words, if we cannot explain something clearly to others, it means we don’t understand it well ourselves. We can confidently explain what we truly know in simple, everyday language. Conversely, when we are unsure, we tend to speak vaguely and repetitively. Those trying to deceive us often use complex language to obscure their meaning.

When such simplicity aligns closely with the laws of nature and life principles, it becomes powerful. Wisdom, inherently, is valuable the closer it is to truth. Religions that have coexisted with humanity and enabled simple living until today can be examples. If these religions did not contain truths or align with the laws of nature, they would not have survived. Though not perfect, their teachings remain relevant. Christianity teaches love for one another, and Buddhism emphasizes compassion. Their principles align well with natural laws. Buddhism’s foundation is that human beings are inherently suffering. All humans must endure birth, aging, sickness, and death, a cycle of suffering.

Everything in the universe is interconnected, spatially and temporally. Therefore, Buddhism teaches compassion for all, acknowledging our uncertain futures. Christianity views humans as bearing original sin, leading men to lifelong labor and women to the pain of childbirth. Despite this, humans continue to sin, and God punishes but also forgives out of love. Therefore, humans should live with gratitude and love one another as God loves us. While these religions may contain deeper meanings, their core principles align with natural laws, advocating effort and unity.

Useful wisdom for living similarly must align with the laws of nature to be enduringly valuable. Phrases like “Know thyself” and “If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles,” have been quoted since ancient times because they are based on natural laws. The world is both a place to be loved and shown compassion and a battleground for survival. If our abilities do not match the given conditions, survival becomes difficult. Hence, knowing oneself and others is the start of survival strategy. Therefore, the answers to “How to think, how to see, and how to act?” can be found in understanding oneself, knowing the enemy, and knowing both oneself and the enemy. We must think according to our abilities, view with the principles of nature, and act in ways that suit the world.

Destiny is no matter of chance. It is a matter of choice: It is not a thing to be waited for, it is a thing to be achieved. ~ William Jennings Bryan

답글 남기기