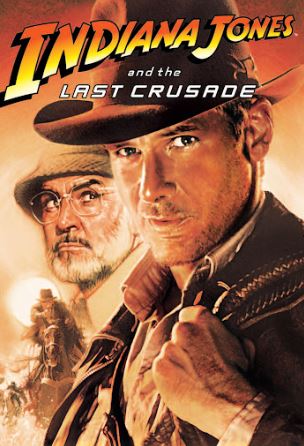

One commonality in action-adventure movies is the need to piece together various clues to find a treasure. In the movie “Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade” (1989), clues hidden in places like the coast of Portugal, north of Ankara, and Venice are combined to find the Holy Grail, which was used by Jesus at the Last Supper. In “National Treasure” (2004), the protagonist, played by Nicolas Cage, pieces together clues from American history to draw a treasure map, like assembling a jigsaw puzzle. The Korean movie “The Mystery Of The Cube” (1999) uses the poems of Yi Sang, which resemble random number tables, to unravel various historical mysteries. The hallmark of such films is that the map or instructions to find the treasure are divided and hidden in multiple parts. Thus, the protagonist must integrate all these clues to complete their mission.

In simple terms, analysis is the process of breaking down complex entities into smaller parts. Synthesis, on the other hand, involves reassembling these parts into a coherent whole. Through analysis, we can filter out redundant or unnecessary information and identify the fundamental substance or cause. To understand the whole, we must synthesize the analyzed parts. Specific methods of synthesis include comparing, grouping, and connecting the pieces. Similar types are classified into categories, and logical relationships are established among the analyzed pieces. Some pieces may be subsets of others or simple components, while some may be causes and others results. During this synthesis process, if there are missing pieces or invisible fragments, we must use “imagination” and “models” to infer the connections. We must ask, “Why so?” or “So what?” when examining an entity revealed through analysis. If known principles and logic are available, the answers may be simple, but if not, we may need to view things from a new perspective or seek help from others.

Creating an integrated understanding requires gathering various perspectives to complete the whole picture. Observing the trees and then recreating the forest is analogous. The periodic table in chemistry and the phylogenetic tree in biology are results of such integration. Knowledge accumulates and wisdom increases through repeated processes of analysis and synthesis. This is why John A. Morrison’s statement, “Knowledge comes by taking things apart: analysis. But wisdom comes by putting things together.” resonates deeply.

Integration employs all the thinking methods discussed so far. Understanding something involves combining all one’s knowledge and experience. While it’s said that one can only understand as much as they know, the ability to integrate knowledge and experience determines understanding. Therefore, being intelligent means having a superior ability to combine the same knowledge others have. Robert Root-Bernstein refers to this integrative understanding as Synosia, a term he coined combining the Greek words for integration (“Syn”) and the act of cognition (“Noesis”). He explains that “the integrative nature of creative understanding is so rarely recognized that there was no appropriate word for it,” thus necessitating a new term.

We learn knowledge through school, daily experiences, and even play. However, this knowledge is only part of what we learn, as we are also learning thinking methods. For example, art is not merely the act of drawing; it involves observing objects, identifying their features, and abstracting their essence, which trains our thinking significantly. Even creating a simple-looking drawing requires observation, analytical skills, shaping ability, and imagination. Such training enhances our capability to perform other tasks. Root-Bernstein emphasizes the importance of art education even for scientists for this reason. Economics trains us to simplify phenomena, while mathematics strengthens our brains through computational thinking. Biology fosters classification skills, chemistry hones analytical and synthetic abilities, and philosophy develops logical thinking. This comprehensive training shapes our thinking capabilities.

Integrative thinking might not solely involve synthesizing one’s own thoughts. True integration includes embracing diverse perspectives from others and combining their findings with one’s original thinking. People gradually integrate the knowledge gained from experiences and learning into their wisdom. This can be done alone or by integrating others’ analyses with one’s own. Much of what I am thinking and writing at this moment is stimulated by others’ thoughts, and parts of my writing may inspire new thoughts in others.

From the time of Aristotle through the Middle Ages, people believed that objects move when acted upon by force and remain still when not. However, Galileo proved that an object continues to move at a constant speed in a straight line if no force acts upon it—Galileo’s law of inertia. Nicolaus Copernicus demonstrated that the idea of the Earth being the center was incorrect. His heliocentric theory inspired Johannes Kepler to discover that the Earth revolves around the Sun in an elliptical orbit, not a circular one. This discovery was aided by the observational data of Tycho Brahe, Kepler’s mentor. Before Newton, people believed that force only acted between touching objects. Thus, the idea of a universal gravitation acting between distant objects was groundbreaking. If universal gravitation exists, planets should be pulled toward the Sun, but they revolve around it. Understanding this requires integrating Newton’s universal gravitation, Galileo’s law of inertia, and Kepler’s laws of planetary motion.

Much of the knowledge we currently have about the world has been achieved through the integration and evolution of knowledge obtained by many people. Originally, knowledge wasn’t as specialized as it is now. With the advancement of knowledge society, academic specialization started, demanding deeper expertise in each field. This kind of advancement greatly developed various fields, especially in science. However, it also resulted in different academic fields having their own languages and ways of thinking, much like building individual Babel towers. But every action has a reaction. There is growing recognition of the need to explore truth through academic integration and to foster holistic insight through comprehensive education.

The attempt to connect natural sciences and humanities into a grand integrative theory is called consilience. Consilience, or 통섭 in Korean, means the unification of knowledge and was a term frequently used by Wonhyo to mean “governing all things.” It’s similar to Root-Bernstein’s concept of Synosia.

Although consilience is not a commonly used term and is being emphasized anew, the phenomenon itself is not new. Great figures like Aristotle, Leonardo da Vinci, and Jeong Yak-yong understood the world through consilience. Although the amount of knowledge at that time was much less compared to today, talented individuals could become consilient scholars. Nonetheless, approaching the truth requires mobilizing research from various fields and methodologies. Choi Chiwon, a scholar from the late Unified Silla period, praised the feats of the Hwarang Namlang in his epitaph, noting that our country’s philosophy was “a combination of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism” with the following record:

“In our country, there is a mysterious path (道) called Pungnyu, which integrates Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, thus educating many people. Devotion to parents and loyalty to the country is like Confucius’ teachings [loyalty and filial piety], silently following reason in all matters is like Laozi’s teachings [non-action], and living earnestly by avoiding evil deeds and adhering to good deeds is like Sakyamuni’s teachings [good conduct].”

In reality, it seems impossible to understand the world through a single academic discipline. The theories of universal gravitation and relativity, which were once thought to explain all the secrets of the universe, still fail to adequately describe the behavior of atoms and subatomic particles. Despite the vast accumulation of knowledge, our understanding of the world remains incomplete. Even well-structured theories cannot explain everything about the world we live in. Austrian scientist Wolfgang Pauli, who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1945, once joked, “How can humans unite what God has scattered?”

Nevertheless, people now strive to approach the truth through integration. Steven Weinberg, an American nuclear physicist, calls this unified principle “Dreams of a Final Theory.” Weinberg’s final theory aims for the grand unification of physics. Edward Wilson’s “Sociobiology: The New Synthesis” attempts to integrate biology and the humanities under the name of sociobiology. More specifically, it suggests expanding the biological principles applied to animals to the humanities and social sciences. Ultimately, understanding humans requires utilizing not only social sciences but also philosophy and discoveries in natural sciences. Social phenomena, classified for research convenience, cannot be as closed-off as academic titles suggest. Just as no reality is isolated from other systems, academic disciplines should not be isolated either. Economics or business studies are merely one perspective of society. To understand the world, we must utilize the achievements of various disciplines such as humanities, economics, physics, and biology. Economic development in a society cannot be achieved solely through monetary or fiscal policies. Understanding people and developing social skills are also essential for economic growth. This is why research reports suggesting that a trustworthy society fosters economic growth are convincing. Although economics is an independent discipline, it is difficult to understand economic phenomena in society without a foundation in the humanities.

This need for integration is not limited to academia. In our daily lives, we also need an integrated perspective. Connecting knowledge and thinking methods from various fields may provide us with tremendous insights. In reality, exams are rarely taken by subject. Everything is a comprehensive test. No problem in this world is confined to a single discipline. Therefore, the more methods we use to think about a phenomenon or object, the better our insights will be. This is why scientists need to train in the arts, writers need to learn science, and painters need to understand music or geometry. Most new things in this world are born this way. Mathematical thinking applied to music, imagination injected into science, and the introduction of natural science knowledge into social sciences have filled the gaps in knowledge. This phenomenon seems to be accelerating. Just as the structure of thought is networked, knowledge also seems to take the form of a network. As the connections gradually increase and everything eventually links explosively, integrating surrounding thoughts and knowledge may create an enormous amount of new knowledge.

In Robert Root-Bernstein’s “Sparks of Genius,” many stories of geniuses are told. A young man who wanted to paint the sun’s halo at the mountain peak became a physicist. A girl passionate about poetry and creating a new world became a mathematician. A young man who loved geometry became an entomologist, and a young social scientist who loved social sciences succeeded as a painter. Such examples are competitive advantages today. Consider the popularity of an artist who draws music, a journalist with a medical degree, or a business executive who studied physics. The MBA program, known for its practical lectures, adopts the case study method. A single business case is used to test knowledge in marketing, strategy, organization, and accounting. Some schools today take children to nature, where they teach biology and physics while explaining the principles of ecosystems and how to coexist. This method fosters effective learning through experience and teaches integrative thinking and perspectives. Such thinking is crucial for us too, as life itself is a comprehensive test of all knowledge.

답글 남기기