The god who governs this world has grown weary. So, he decides to take a week-long vacation. Unlike the Dark Ages when he left the region called Europe unattended for a long time, this time he calls upon a complainer named Bruce to take over some of his duties in New York.

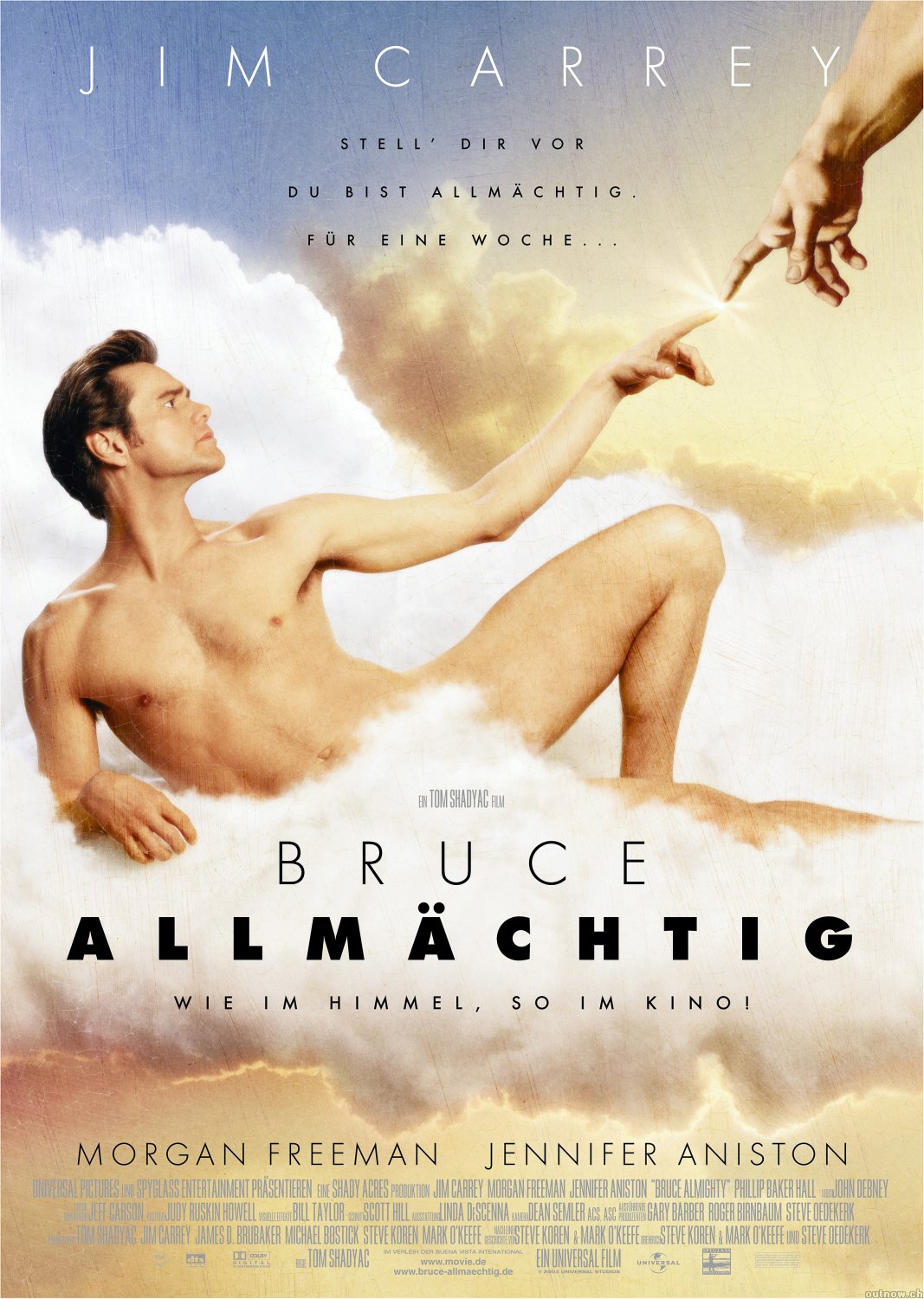

This is the story from the 2003 comedy film Bruce Almighty starring Jim Carrey. Bruce is a news reporter at a local station in Buffalo, New York. He feels unappreciated at work and things never seem to go right for him, leaving him perpetually disgruntled. He blames God for his misfortunes, shaking his fist at the sky. On the day he fights with his girlfriend Grace (Jennifer Aniston), his complaints escalate into blasphemy. “If there’s a God, then answer me! Aren’t you the only one who gets to sit around doing nothing while I suffer?” One day, Bruce receives a pager message displaying the number 555-0123. After ignoring it several times, he finally calls back and meets a janitor (Morgan Freeman) who introduces himself as God. God offers Bruce his almighty powers while he’s on vacation. Bruce, wielding his newfound powers carelessly, turns the world into chaos. When Bruce, anguished by the havoc he caused, seeks forgiveness, God tells him:

“People want me to do everything for them. What they don’t realize is that they have the power. You want to see a miracle? Be the miracle.”

People often attribute the source of human miracles to the subconscious mind. They explain that the astonishing abilities people display when they fervently desire something or find themselves in critical situations come from this subconscious power. Authors of best-selling self-help books like Robert Collier, Napoleon Hill, and Claude Bristol emphasize that we all possess miraculous unconscious abilities, which are activated through belief, positive thinking, and the magnitude of our thoughts. But do such abilities truly exist within us?

It’s said that our long-term memory capacity is roughly 1,000 times greater than that of a personal computer, and the density of the human brain is actually about 1,000 times greater than a computer. While methods for calculating human memory capacity are highly arbitrary, density can be measured relatively objectively. In this sense, our brain is vastly more complex than a computer. Each of the approximately one hundred billion nerve cells in the brain has numerous branches unlike regular cells. These branches connect to other cells. The connection between one nerve cell and another is called a synapse. On closer examination, the ends of the two branches are not fully connected but are separated by a tiny gap. Certain substances bridge this gap, namely neurotransmitters like serotonin, noradrenaline, and dopamine. When an electrical signal travels along a nerve cell’s branch to the end, it releases these chemicals, which swim across the synaptic gap to transmit information. No matter how large, a computer cannot compare to the complexity of the synaptic network in the brain. Perhaps the secret to our potential lies hidden in this complexity of the human brain. However, there are special abilities we already know we possess: the abilities to learn and imagine.

There is a fundamental difference between how digital computers process information and how the brain does. Despite terms like AI and deep learning becoming commonplace, computers fundamentally lack learning abilities. Humans, on the other hand, can use learned facts and principles to solve new, unlearned problems. Computers do not inherently possess this type of learning ability. Expert systems can replace humans in certain tasks, but they do not learn independently. For example, a diagnostic expert system for patients applies knowledge input by doctors according to programmer-defined rules. So where does this human learning ability come from? It stems from the capacity to combine seemingly unrelated information—a quality called imagination. Ultimately, our learning ability is rooted in our imagination.

The results of chess matches between humans and supercomputers, which began in 1997, suggest that there is something unique about human abilities. Today’s computers can analyze millions of moves per second. Yet, humans can still hold their own against these machines. While these matches primarily showcase the advancements in computer technology, they also remind us that humans possess some inherent potential. For example, in simple chess matches, humans and computers are still evenly matched. However, in Go, computers lag behind humans, and in poker, humans remain dominant. Poker involves uncertainty about the next card, introducing an element of luck. In Go, intuition and momentum often determine the outcome. The fact that humans can still compete with supercomputers is due to our intuition, the concept of “feeling,” and strategic abilities such as bluffing.

For Freud, who first introduced the concept of the unconscious, it was a form of repressed consciousness. In other words, painful, unacceptable, or improper thoughts were suppressed and exiled to the unconscious. However, modern psychology views the unconscious as an indispensable part of our daily lives. Freud likened consciousness to the tip of an iceberg, indicating that most of our mental activity is unconscious. Timothy Wilson, author of “Strangers to Ourselves,” suggests that consciousness is not even the tip of the iceberg but merely a snowball on top of it. He defines the unconscious as mental processes that do not reach consciousness but influence judgments, emotions, and behavior. When we attribute latent abilities to the unconscious, it becomes the subconscious. Experts in success and religion teach that to awaken the subconscious as a potential ability, one must employ meditation, prayer, or seated meditation with belief and faith. While these methods depend on individual beliefs, they are not baseless. The unconscious and subconscious are no longer abstract concepts but real phenomena.

The concept of immersion is emphasized as a way to enhance our thinking abilities through the subconscious. Immersion means focusing intensely. While some claim that only they can experience this special state, the truth is that everyone can experience it. The term itself implies a state of deep concentration on an activity, which is a common experience. Discovering a new method of expression does not mean discovering a new world. Nevertheless, deeply concentrating on an activity to the extent of forgetting the flow of time, space, and self is called the state of immersion. Everyone experiences this to some degree, such as when reading a book without noticing time passing, focusing on a favorite activity, or being engrossed in a game.

Particularly, reaching a state of immersion while reading has long been known as “the trance of reading.” “Trance” refers to the highest level of mental concentration achievable by humans. Engaging in deep conversations with a loved one or being lost in music are also forms of immersion. Erich Fromm, author of “The Art of Loving,” defines love as interest, understanding, knowledge, care, and immersion in an object. Thus, the state of immersion can be seen as being engrossed due to love, which is a universal experience. When we enjoy what we do, our performance and creativity naturally improve.

Psychologist and educator Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls this state “flow,” defining it as a feeling of flying freely or moving as smoothly as flowing water.

We often experience similar states when we need to finish something within a time limit, such as preparing for an exam, writing a thesis, or completing work tasks on time. However, Csikszentmihalyi argues that while focusing on a goal is similar, it is not the same as reaching the state of immersion. True immersion must be inherently rewarding and not driven by the need for reward or fear. The act of thinking itself should be the reward, as this enjoyment activates our brain. Our brains thrive on enjoyable, interesting, and novel activities. The hippocampus and amygdala, which are responsible for memory and emotion respectively, are located next to each other, indicating their close relationship. Enjoying the process is essential to reaching immersion, just as love and immersion go hand in hand.

It is difficult to experience true immersion in an anxious state driven by deadlines, superior pressure, or work stress. Conversely, it is also challenging to achieve immersion with a listless attitude due to lost interest or goals. Immersion, or “flow,” is best experienced when our minds are balanced between boredom and anxiety. Professor Hwang Nungmun, author of “Immersion,” describes this as the state of “Slow Thinking.” Unlike computers that excel in speed, our brains are powerful when thinking slowly. Evidence suggests that our brains function better with slow thinking, as the level of brain activity differs between slow and fast thinking.

Human brainwaves are known to consist of four types: beta, alpha, theta, and delta. These waves are measured by amplifying the faint electrical signals from the brain. Beta waves dominate when we are excited or tense, while delta waves appear when we are sleepy or sleeping. In contrast, alpha waves are found during relaxed, slow thinking. This placement of alpha waves between beta and delta waves indicates a semi-sleep or meditative state. When we engage in immediate and urgent thoughts, only beta waves are observed, characterized by complexity and lack of rhythm. Conversely, when we are immersed or in a meditative state, rhythmic alpha waves are generated. These waves also appear during meditation, when moved by nature or art, or when struck by a good idea.

The experience of flow aligns with the state of being neither too tense nor too bored. Alpha waves sit between the tension of beta waves and the sleepiness of delta waves, representing the optimal state for memory and concentration. This is because alpha waves are associated with the secretion of endorphins. Endorphins, known as natural opiates produced by the body, are secreted when we feel refreshed, happy, or genuinely loving. Thus, releasing alpha waves indicates endorphin secretion, explaining why those experiencing flow feel relaxed and joyful.

Achieving the states of immersion and meditation makes the mind calm and slows brain activity, producing alpha waves. However, meditation and immersion are not the same. Meditation is a mental and physical training method, while immersion is a self-development activity aimed at achieving goals. Additionally, meditation focuses on emptying thoughts, whereas immersion involves active thinking. Immersion is about concentrating on problems and finding solutions, which is what interests us. To reach the state of immersion, the goal must be challenging but not stress-inducing.

The more interesting and valuable the challenge, the more we want to immerse ourselves in it. In any challenge, finding even a small clue in the immersion process can spark motivation and a sense of achievement. This satisfaction is more enduring and productive than simple pleasure. Dopamine plays a significant role in this feeling of satisfaction. Known as the chemical of motivation and reward, dopamine is secreted when we are eager to start something new. This explains why the anticipation before a trip often feels more exciting than the trip itself. However, excessive dopamine secretion can deplete energy and potentially lead to issues like schizophrenia. The premature deaths or mental illnesses of stressed geniuses and entrepreneurs may be linked to excessive dopamine secretion.

We often meet people who are “crazy” about their work, meaning they are intensely focused. Such focus can bring joy but can also lead to work addiction and stress-related harm. Fortunately, when immersion is driven by personal enjoyment, endorphins are also activated. This is a great fortune for dedicated individuals because the combination of a small amount of dopamine with endorphins amplifies the effect without significant side effects. This ideal state of immersion is the most effective way to use our brains. The best time is when we feel challenged yet eager to enjoy the process.

We encounter such situations regularly. Playwright Bernard Shaw and his contemporary, American actor-producer Arnold Daly, summarized the essence of immersion simply:

“Golf is like a love affair. If you don’t take it seriously, it’s not fun; if you take it too seriously, it breaks your heart.”

Both golf and love should be enjoyable challenges. In such cases, we can easily immerse ourselves, making the activity itself a pleasure. In sports games, if the opponent is much weaker than us, we cannot immerse ourselves, and the game becomes less enjoyable. However, playing against a well-matched opponent is different. We can enjoy the game and feel a great sense of accomplishment if we win. Immersion occurs when we encounter a “pleasant challenge” and focus on it. This process can yield greater results than usual, showcasing the effects of immersion.

Experts on immersion argue that geniuses like Newton and Edison made their discoveries and inventions through immersion. While we cannot verify this, it is undeniable that they intensely focused on something. When we deeply think about one thing, solutions to seemingly unsolvable problems may arise, and extraordinary ideas may emerge, seemingly out of nowhere. This is a common experience for everyone.

The benefits and effects of immersion are well-known. Whether studying or working, we perform better when we focus. The same is true for sports, where there is a clear difference between those who concentrate and those who do not. At the highest levels of athletic competition, every game becomes a mental game. The skills of the world’s top athletes appear almost identical; the difference lies in whether they can focus at critical moments. Immersion primarily means a state of concentration. Such a skill is a habit, developed through training and reinforced by confidence. This is why professional golfers combine mental training, like meditation, with physical training. Ben Hogan, a legend in American golf, said, “Golf is 20% skill and 80% mental.” Jack Nicklaus emphasized the importance of mental skills, claiming, “Golf is 90% mental.” The core of these mental skills is concentration.

Being able to immerse yourself in every given moment is ideal. We can expect consistently better results. However, the nature of immersive thinking requires time because it involves slow thinking. Our conscious thinking is not instantaneous, and focusing on a problem consciously seems to take considerable time, unlike physical labor. It is not easy to tackle a problem immediately after arriving at work in the morning. Writing is even harder; we need to tidy our desks and make efforts to delve deeply into our thoughts, requiring a sort of mental warm-up.

Experts advise creating time for immersion, even if forced. Microsoft’s Bill Gates is famous for his “Think Weeks,” where he spends a week twice a year in a remote cabin, solely to think. We, too, take trips and breaks occasionally. During such times, we reflect on important life issues. However, we can also attempt to immerse ourselves in a specific topic during our daily lives. Initially, it should be in a relatively quiet and solitary place, but once we start immersing, we can focus on a topic even while moving around. This is something everyone experiences at least once. Our conscious thoughts gradually enter a state of immersion, allowing us to think about the topic while commuting, eating, or waiting for friends in the evening. This is how we can utilize the thinking skill of immersion in our daily lives.

Consider someone reading a newspaper on the subway, inconveniencing others. All they gain is simple information or fragmented knowledge, which is necessary for life. However, if they deeply think about a chosen topic during that time, they might gain truly important wisdom for their lives without disturbing others. This premise assumes they are thinking about specific, solvable problems or propositions, not random thoughts. Simply reading something is not enough; as emphasized, neglecting the thinking process while prioritizing reading should be avoided. What we truly need comes from immersing ourselves in thought.

Both meditation and immersion involve entrusting some of our conscious tasks to the unconscious. Utilizing all the information in our unconscious consciously seems experientially challenging. However, it is true that our memory stores all our past experiences as vast knowledge. Immersion involves a chain of thoughts, where one thought leads to another. During this process, ideas stored unconsciously may emerge, connected in new ways to solve problems we are focusing on. This is why we immerse ourselves in problem-solving.

People spend about a third of their lives sleeping. If we could utilize this time, it would be a significant competitive advantage. Although the primary purpose of sleep is rest, allowing our bodies to recharge by reducing physical activity and lowering body temperature, our brains do not fully rest during sleep. Sleep cycles vary in depth, with the deepest sleep occurring 30 minutes to an hour after falling asleep. After an hour, sleep lightens and maintains this state, with a brief deep sleep just before waking. Brainwave studies reveal that during the deepest sleep, brain activity is minimal, indicating rest. However, even in deep sleep, some brain activity occurs, showing that our brains never fully rest. REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep, where we dream, features brainwaves associated with memory and well-being, such as alpha and theta waves. During REM sleep, our brains organize information, much like a computer sorting and deleting files. This process involves discarding unnecessary memories and negative emotions and transferring short-term information to long-term memory. Protein synthesis increases during REM sleep, supporting memory-related activities.

Immersion involves utilizing the brain’s activities during sleep. Although new information cannot be acquired while sleeping (e.g., listening to English tapes does not result in learning), our brains work with existing memories. Reviewing important information before sleep can aid memory retention, as crucial information might be organized during sleep. Deeply thinking about a current topic before sleep is another method, potentially allowing our subconscious to work on it overnight. Sometimes, ideas or solutions emerge in dreams, providing evidence that our brains were actively thinking during sleep.

Renowned ideas and inventions often emerge from dreams, known as serendipity. While some discoveries result from accidental failures during experiments, like Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin, immersion can also lead to serendipitous results. This applies to everyone to some extent. For instance, German chemist F. A. Kekulé discovered benzene’s molecular structure after dreaming of atoms forming a snake biting its tail. Immersed in thinking about a problem, stored unconscious information may connect in new ways, leading to unexpected results.

Immersion is a thinking skill that draws inspiration and utilizes our unconscious or subconscious. Psychologist Carl Jung suggested that our lives might be a “history of the self-realization of the unconscious,” implying that many answers lie within our unconscious.

답글 남기기