In my competition, factors such as the environment I work in and the people I collaborate with within an organization are crucial. This environment is a must for any formula or secret to success. Indeed, in many cases, who you work for can be more important than how well you perform your job. Consider the concept of tournament competition, which is our primary form of competition. The tournament you participate in sets the initial conditions, and these conditions can determine the rest of your life.

Once you’ve developed your talents and acquired core competencies, you must then find a market where these skills can be utilized. While skill is an important factor, competition isn’t merely about skill alone. As you progress through the tournament, the rules of the game gradually change.

One significant aspect of these changing rules is “queueing.” In many societies, queueing is viewed negatively as a rule of the game. However, in reality, queueing exists in all societies. For corporate executives and CEOs, queueing is decisive. It’s not the difference in skills that matters but which side you stand on and whether it benefits you, turning competitors into either collaborators or adversaries.

For politicians, queueing is an even more crucial rule of the game. Most politicians we meet have started their careers through queueing. From the outset, their strategy has been centered around queueing. For a parliamentarian, their political fate is often decided by the party they choose, the faction they belong to, and the specific individuals they support. With terms like “pro-Park” or “pro-Lee” openly appearing in the media, we cannot consider queueing as merely unfair.

Queueing, from a job seeker’s perspective, involves deciding which company to work for, and for a merchant, it involves deciding what business to conduct and where.

On a larger scale, it also involves deciding which network to join. In the realm of competition, we must start with the conviction that there is nothing we can accomplish entirely alone.

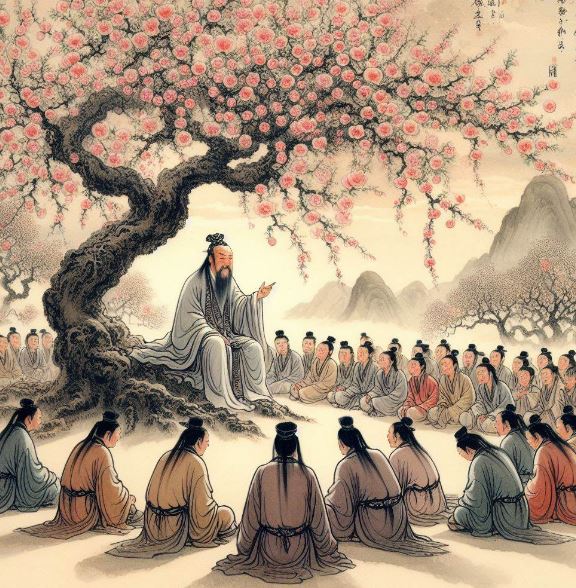

Success can also be determined by whom you meet and how well your own competitiveness shines through. In this regard, Confucius could be said to have found his competitive edge in teaching. From the age of 55, Confucius traveled the world for 14 years, seeking opportunities to share and implement his political philosophy and ideas.

However, no ruler ever entrusted Confucius with a significant position, though he had many disciples eager to learn from him. One day, his disciple Zilu asked him, “If there were a beautiful piece of jade here, would you hide it away or seek a merchant who would appreciate and pay well for it?” Confucius replied, “I would sell it, sell it,” and added, “I am someone who waits for the right owner to value it properly.”

Yet, Confucius’ competitiveness was not in managing a state but in teaching people. He eventually became a great teacher, leaving a lasting legacy in human history. But even he had to wait for someone to recognize his competitiveness.

The story illustrates how meeting the right person or place to leverage your competitiveness can make all the difference. Everyone needs to prepare to meet those who truly appreciate them, waiting with skill, integrity, and passion for their opportunity to be recognized, as was the case with Jiang Ziya.

The nature of competition within groups is entirely different from head-to-head competition. We often refer to this as political. People in groups emphasize harmony and try not to make enemies. In such societies, having unseen allies is a crucial competitive advantage.

Moreover, being well-positioned in line is about having opportunities. Without opportunities, one might lose the chance to demonstrate their abilities. In fact, success often seems to depend on luck, which refers to the social phenomenon of “seven parts luck, three parts skill.” However, if luck isn’t predetermined as fatalists claim, it might be possible to analyze and identify the factors that make up luck. And if you can find it yourself, then what we call luck might not be luck at all.

It’s not impossible to either improve or worsen our luck. Let’s save this discussion for another time, but it’s reasonable to assume that luck depends on the opportunities we seek.

Malcolm Gladwell in “Outliers” explains various factors of success but emphasizes that ultimately, people’s success depends on luck. And this luck comes in two kinds: one is the random opportunities that life presents, and the other is the type of luck that comes from being part of a social group like a family or a nation. Some of these can be changed over time, so ultimately, both types of luck are related to opportunities.

Once someone has an opportunity, it can lead to cumulative benefits in our society. For instance, someone who randomly wins a lottery and earns a billion might, with a bit of wisdom, turn that money into more, making it increasingly difficult for others to catch up. This shows how a small initial difference can lead to significant disparities.

You might randomly meet a great teacher or join a superior educational group or community, securing a better opportunity than others. That’s why there’s a saying to send people to Seoul and horses to Jeju. Although it might seem like chance, figures like Sun Myung Moon of the Unification Church and Park Tae-Seon of the religious group Sinangchon, who both came from Christian families in North Pyongan Province and were disciples of Kim Baek-moon from the Israeli monastery, had unique learning opportunities that distinguished their growth from others.

In South Korea, tycoons like Lee Byung-chul of Samsung, co-founders Koo In-hwoi and Heo Man-jong of LG, and Cho Hong-je of Hyosung all share something in common: they lived near each other in the same town or neighboring towns near Jinju, Gyeongsangnam-do, and all attended Jisu Elementary School. While geomancers might claim that the Namgang River in Uiryeong influenced their fortunes, it’s more likely that these individuals shared critical information about becoming wealthy and that the changing times provided them with opportunities to become wealthy.

Globally, Malcolm Gladwell also points out that the opportunities presented by one’s era are the most crucial factor for success. For example, Bill Gates of Microsoft, Steve Jobs of Apple, Eric Schmidt of Google, and a child born in Korea in 1955 all share the fact that they were born in 1955. The pivotal year in the history of the computer revolution was 1975, which saw the introduction of the Altair 8800, the world’s first commercially available mini-computer. In 1975, these individuals were all 21 years old. However, a child born in Korea at that time would not have had the same access to information or opportunities. Probably, the personal computer was something they only saw when entering college in the early 1980s.

Today might seem different, as information spreads quickly and is widely shared, suggesting that geographical differences might not be a significant factor. However, according to research by scholars like economist Adam Jaffe, knowledge tends to be concentrated in specific regions because of educational and training opportunities. Joining a tournament or league means you are at a place where you can train and learn during that period.

Therefore, Malcolm Gladwell argues that the success of the Beatles was because their band had the opportunity to play nightly in Hamburg, Germany. Though the pay wasn’t great and the sound equipment wasn’t the best, their daily performances provided them the chance to refine their skills, ultimately making them one of the greatest rock bands.

Gladwell concludes that Bill Gates and the Beatles, though naturally talented, were distinguished not by their talents but by the extraordinary opportunities they had. Such opportunities might be stumbled upon by chance, but they are more easily accessed by those who actively seek them out.

답글 남기기