Former Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev used the German proverb “Trees don’t grow to the sky” to emphasize that there are limits to growth. On Wall Street, this expression is used to indicate that stock market prices cannot increase indefinitely. Wealth accumulates where it already exists, and more information is amassed by those who already have it. Complete equality does not exist. Those who already possess money and information not only exert their own efforts but also see their money earn more money and their information gather more information. Imagine lions of the same size in a jungle. If one happens to consume a lot of food early on, it grows larger and develops a superior ability to catch more prey, growing even larger. This is called positive feedback.

However, this phenomenon does not continue forever. Eventually, the fatter lion will slow down, and the wealthy may become lazy or make mistakes due to arrogance. The poor incur debts and must pay interest on the earnings from their labor, progressively becoming poorer. This can be described as negative feedback. Yet, those who take these difficulties as lessons and strive hard may seize opportunities and generate positive feedback. This is a type of cyclical phenomenon that continues to occur, driven by both positive and negative feedback.

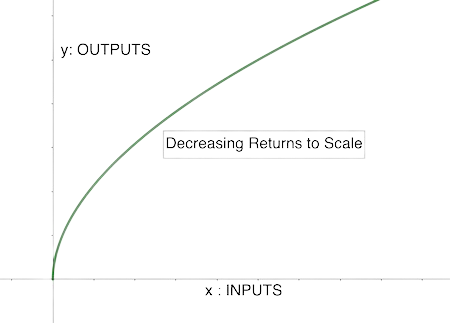

In fact, the world of traditional economics is governed by the law of diminishing(decreasing) returns to scale. Diminishing returns occur when, keeping other inputs constant and increasing the amount of labor, the overall production increases but the marginal increase in output per additional unit of labor gradually decreases. For example, as more workers are employed on a fixed amount of farmland, the yield per worker gradually decreases.

Economists recognize that both increasing and diminishing returns can occur, yet they generally observe that diminishing returns are more prevalent in practice. Alfred Marshall, who established this concept, lived at a time when industries frequently encountered diminishing returns. This was especially evident in the production of natural resources, where the stages of diminishing returns were quickly reached due to the predominance of variable costs.

In the knowledge economy, the phenomenon of increasing returns to scale becomes more prominent due to high development costs. In fact, much of the real economy operates under increasing returns, especially in industries with high technological intensity, where such phenomena persist longer.

With the advancement of computers and the emergence of digital economics as a new method of value production, the notion of increasing returns started to take hold. People began to believe that a new economy characterized by persistent increasing returns had emerged. Specifically, Stanford University economics professor Brian Arthur highlighted that while the law of diminishing returns governs traditional mass production systems that consume substantial agricultural or natural resources, the development of cutting-edge technology and knowledge-based production systems leads to the opposite phenomenon—increasing returns.

However, the law of increasing returns is a general phenomenon that appears in most situations requiring cooperation, not just in high-tech industries but also in traditional industries. Just because it is more visible in the digital economy does not mean it is a new theory.

The immense initial development costs lead to economies of scale, where the more units sold, the lower the cost per unit. This phenomenon is also common in large-scale industrial operations, not just new technology industries.

The term ‘increasing returns’ might not have been used in the past, but the phenomenon has always been present. Consider the concept of ‘economies of scale’, which refers to the reduction in production costs and increase in profits as production scales up, primarily because average costs decrease. The larger the development or fixed costs, the more persistent the increasing returns, as average costs continue to decline, and marginal productivity keeps rising.

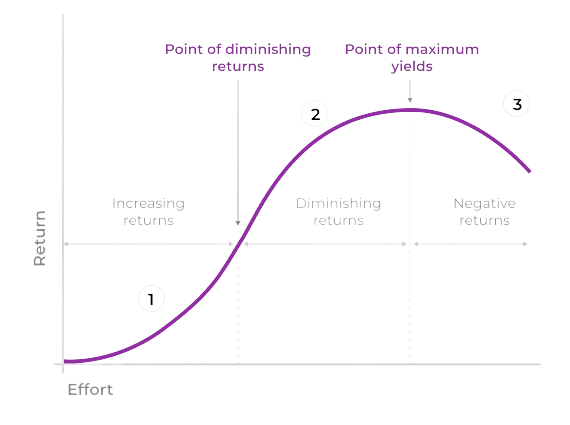

The productivity and efficiency gains from increasing returns are similar. Although some argue that the new economy has shifted from an era of diminishing returns to one of increasing returns, these too have their limits. Depending on the nature and structure of the market, productivity may eventually decrease. For example, huge corporations that have grown too large may lose competitiveness due to reduced flexibility and speed.

In production dependent on labor and resources, there comes a point where the costs of managing additional inputs can increase more readily than the profits from increased production inputs. Consider a simple example where many people working together might lead to complexity, confusion, and conflict. At some point, additional fixed and management costs may arise.

Eventually, there might be instances across all fields where negative synergies occur, and the law of diminishing returns becomes evident.

In fact, increasing and diminishing returns can alternate. In a world where inputs and outputs influence each other, a constant ratio between them is rather an exceptional case. Most phenomena we encounter, as discussed by complexity scientists, involve non-linear relationships.

At a certain stage, not only may marginal productivity decrease, but the overall production may also decline. This means that increasing the number of production inputs does not necessarily lead to a continuous increase in output. If too many people are working in a confined space, they might interfere with each other, reducing productivity. Simply gathering people does not automatically strengthen their collective power. How these people are united and organized is crucial. In other words, to sustain increasing returns, deliberate design and organization are necessary.

There is a saying, “오합지졸(烏合之卒)” which means a disorderly crowd of soldiers, similar to a gathering of crows, signifying a hastily assembled, undisciplined, and chaotic group. Just having many such soldiers does not make the overall force stronger. Training is needed to organize them and unite them into a single powerful force. Similarly, having many people in a company does not guarantee better ideas. Without a willingness to learn, an openness to inspire and be inspired by each other, there might only be misunderstandings and conflicts. Both synergistic effects and the law of increasing returns are not obtained for free.

답글 남기기