Languages in the world can be broadly divided into isolating, agglutinative, and inflectional languages.

Inflectional languages = Words themselves bend or twist, changing in form.

Agglutinative languages = Part of the word is replaced, conveying various meanings.

Isolating languages = Words themselves do not change, only their position changes.

This classification is referred to as classification based on the morphological typology of languages. Although it might sound complex, ‘morphology’ here refers to the form of words, essentially meaning that languages are classified based on how the appearance of words changes when they are created and used.

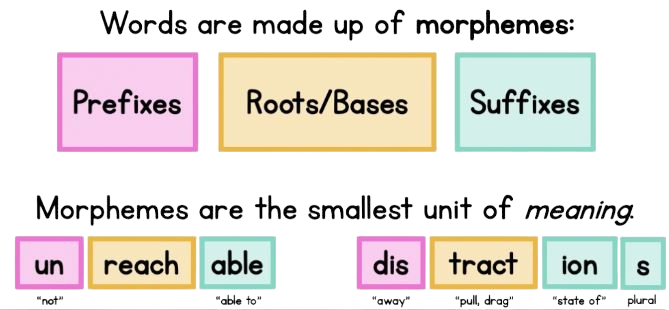

All languages in the world fundamentally possess the smallest meaningful units of speech known as morphemes. And as defined, words are formed by combining these morphemes. For example, in English, the word ‘unreachable’ is composed of three morphemes.

Morphemes are the smallest units of speech that carry meaning and cannot be further divided without losing their meaning. For example, ‘apple’ is a single morpheme that cannot be divided into smaller parts without losing its meaning. If you were to divide ‘apple’ into ‘app’ and ‘le’, it would lose its significance. On the other hand, ‘apple tree’ is a word composed of two morphemes, ‘apple’ and ‘tree’.

Classifying the languages used on this planet according to their forms essentially means dividing them based on how morphemes are combined and utilized. The world’s languages can be categorized based on the method of assembling words.

Specifically, a language that forms words from a single morpheme is called an isolating language, whereas a language with words that contain multiple morphemes is referred to as a polysynthetic language. Morphemes can include those that signify tenses like past, present, and future.

Chinese is a typical example of an isolating language. In contrast, languages used by the Maori people (Te Reo Māori) where a single word can carry a sentence-level meaning and length, are examples of polysynthetic languages. In fact, many languages fall into this polysynthetic category since most languages, as exemplified by ‘unreachable’, are made up of more than one morpheme.

Isolating Languages Isolating languages are characterized by their words being composed of a single morpheme. However, a more important feature is that this form does not change even when creating different types of sentences. A word in such languages is akin to a piece of LEGO, and forming a sentence is like assembling these LEGO pieces; that is, there’s no need to alter the words when making sentences.

Therefore, in isolating languages, the meaning changes not because of the alteration of the word itself, but due to its position in a sentence, as seen in Chinese. For example, by changing the word order in “我爱他.” and “他爱我.”, you can express “I love him.” and “He loves me.” respectively, without altering the form of the words, adding particles, or changing the verb endings. Naturally, there are no changes in the verb for tense or person. Thus, isolating languages might seem easy to learn at first since one only needs to know the words. However, this simplicity comes at the cost of considerable effort in interpretation.

Polysynthetic Languages

Languages that use words made up of two or more morphemes can all be called polysynthetic languages. The Maori language used by the Maori people of New Zealand is cited as an example of a very complex polysynthetic language. The following long word is the name of a hill on the North Island of New Zealand:

Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateapokaiwhenuakitanatahu

This word translates to “the hill where Tamatea, the man with big knees, the climber of mountains, the land-swallower who travelled about, played his flute to his loved one.” How can one possibly remember such a word?

When learning a language, what matters more is whether and to what extent words change when forming sentences with these words. Thus, polysynthetic languages are further classified into inflectional and agglutinative languages based on how words change when creating speech. The criterion for this classification is “How much does a word’s morphemes change according to the sentence, or from the opposite perspective, how much of its original form is maintained?” If the morphemes are relatively visible in the sentence, it’s an agglutinative language; if not, it’s considered an inflectional language.

Inflectional Language

Languages in which words change significantly according to the sentence fall under inflectional languages. Inflection means change. Inflectional languages typically alter the word form according to grammatical categories such as gender, number, case, person, tense, aspect, mood, voice, etc.

Take, for example, the following expressions in English:

I love him. He loves me.

The subject forms are I and He, but they change to me and him in the objective case. This change is known as inflection. Such changes in English are actually few. In contrast, in German and Latin, the changes in words according to gender, number, and case are far more numerous and complex than in English.

Fortunately for English learners, English has evolved from an inflectional to an isolating language. There are remnants of irregular verb forms and case in pronouns, but sentences are formed by assembling words like LEGO pieces without changing the words themselves.

Agglutinative Language

Between inflectional and isolating languages, there are agglutinative languages, which undergo many changes but relatively in a rule-based manner. Both nouns and verbs change in the sentence, but the original form, the morphemes, remains clear, and the changes themselves are regular. Academically, the inflection of nouns is called declension, and the inflection of verbs is called conjugation, but essentially, it means they change.

In inflectional languages, the same word often changes as if it were a completely different word, whereas in agglutinative languages, the words change slightly at the beginning or end to convey subtle meanings. Japanese and Korean are examples of such languages.

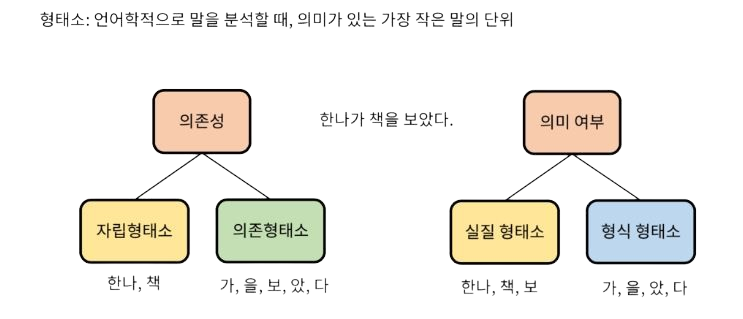

In the example sentence “Hanna saw the book,” there are changes due to particles such as ‘가’ and ‘을’ for nouns, and for the verb ‘보다,’ the sentence is formed through the addition of the past tense suffix ‘았’. This demonstrates that, although there are changes, the language does not become completely different, which is characteristic of an agglutinative language. Compared to inflectional languages, the combination of morphemes is looser, leaving the root of the word, the original morpheme, intact.

English Vs. Korean

Now let’s compare English and Korean, our main points of interest. Korean is an agglutinative language, whereas English, which was once an inflectional language, has now become an isolating language. Of course, traces of inflectional and elements of agglutinative languages coexist in English.

Traces of English as an inflectional language can be seen in irregular changes. For instance, ‘I’ and ‘me’ are difficult to claim as having a common denominator. However, the past tense suffix ~ed that attaches to verbs like a tail and the ~s that attaches to third person singular verbs are similar to changes in agglutinative languages, making them regular changes.

Thus, while there are traces of inflectional and agglutinative languages in the forms and conjugations of verbs, the more dominant feature of modern English is that of an isolating language, similar to Chinese, where the meaning is conveyed more by the position of words in a sentence rather than changes to the words themselves.

In fact, English belongs to the Indo-European family and was fundamentally an inflectional language. However, as various words came together and English itself was reorganized, it seems to have solidified into a lexicon-centered language. A lexicon-centered language means an isolating language. Once again, from the learner’s perspective, this is indeed very fortunate.

답글 남기기