In the year 2505, America is full of fools. Even the president has an IQ that does not exceed 100. This is the world depicted in the movie “Idiocracy, 2006”. Idiocracy, a portmanteau of “idiot” and “cracy”, can be interpreted as “the rule of fools”. The educated elite increasingly avoid having children, leading to a population decline, while the lower social classes prolifically produce offspring, whose descendants exponentially increase. As a result, 500 years later, America becomes a world populated by people with inferior intellectual abilities. Of course, this movie is an absurd satire.

Considering the vast amounts of information that would be digitalized 500 years from now, how could such a world come to be? Unlike the balanced Vitruvian Man by Da Vinci, the appearance of people holding remote controls, beer cans, joysticks, and wine bottles with protruding bellies in the movie’s poster explains the reason well. Joe (Luke Wilson), the protagonist of “Idiocracy”, wants to convey the following message to the people of today who dislike thinking:

“Tell people to read books. Tell them to stay in school. Tell people to just use their brains or something.”

Having a lot of information does not necessarily make one smart. Not all information becomes knowledge, and having a lot of knowledge does not always lead to wise decision-making. While information and knowledge have different meanings in academic contexts, in our daily lives, having information and knowledge typically qualifies someone as being smart and knowledgeable. Yet, pretenders to intelligence are everywhere. Most of us living today possess far more information and knowledge than intellectuals of the past. Excluding creativity, it might be fair to say that we are smarter than them. We live in an era where middle school students are aware of the theories of universal gravitation and inertia discovered by Newton. Not only knowledge acquired through formal education but also information obtained from TV dramas, documentaries, and the internet is vast. Hence the term “the sea of information”.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) introduced the term “knowledge-based economy” in a 1996 report, a concept now familiar to us all. A knowledge-based economy is defined as an economy where “the creation, dissemination, and use of knowledge and information are key to all economic activities, as well as to creating added value for the nation and competitiveness for businesses and individuals”. In short, it is a society where knowledge, rather than labor or capital, is the source of wealth. The OECD also categorizes knowledge into four types: factual knowledge (Know-what), theoretical knowledge (know-why), procedural knowledge (Know-how), and personal knowledge (Know-who).

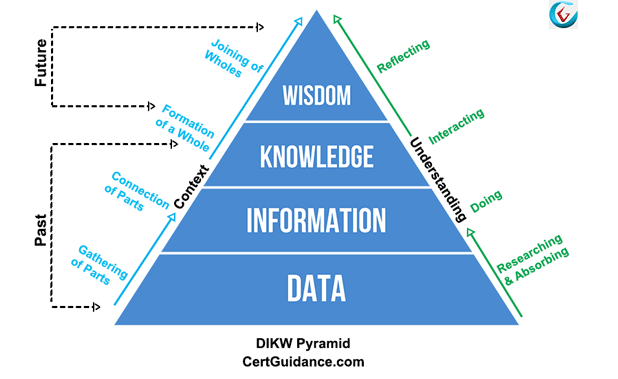

Factual knowledge refers to knowing specific ‘facts’ (What). These are generally what we call information. What we usually seek or obtain in our daily lives is data or information. Data, in its raw form, is unprocessed numbers that have not yet been systematized, analyzed, or generalized. When this data is organized with some purpose or meaning, it becomes information. If we collect only the data we need, that too can be considered information because it is meaningful to us. For example, the red, yellow, and blue lights of a traffic signal are merely data in themselves. However, when we assign meanings like stop, wait, and go to these lights, they become ‘information’. Now, we interpret the information of the traffic light’s colors and decide our actions based on this information.

Here’s another example: suppose a local supermarket sells a bottle of soda for $ 1, while the same soda is sold for $0.7 at a large discount store that requires driving to. The prices of $1 and $0.7 at each store are data. If we understand that the soda is $0.3 cheaper at the discount store than at the supermarket, this becomes very useful information. Thus, information has purpose and meaning. Information about ‘who knows what and how something is being done’ can specifically be classified as personal knowledge (Know-who). In today’s era of highly specialized labor, where different knowledge and skills widely cooperate within networks, this type of knowledge is increasingly valuable. The term Know-where, which we sometimes use, would also fall into this category.

Moving beyond the level of ‘knowing’ something to ‘understanding’ the reasons or causes behind its operation means we possess theoretical knowledge. Theoretical knowledge (know-why) is knowing the laws and principles of natural movement, human psyche and behavior, and social change. This knowledge is often readily accepted by many people because it has been granted a form of authority. Although knowledge and information are almost used interchangeably in daily language, knowledge is more generalized and enduring than information. There isn’t a specific form for information and knowledge; what is merely information to one person can be knowledge to another, and something can be information in one context but knowledge in another.

For information to become knowledge, it needs to be analyzed, synthesized, and generalized. More specifically, this transformation from information to knowledge happens through processes like deconstruction, comparison, connection, and verification. As a result, knowledge becomes systematic and gains universal validity, meaning it is generally acceptable. For instance, understanding not just that discount stores are cheaper than local supermarkets but why they can sell at lower prices due to economies of scale means you possess knowledge.

There’s a difference between ‘knowing’ and ‘understanding’, but ‘doing’ is an entirely different dimension. Procedural knowledge (know-how) pertains to the capability to do something. We derive procedural knowledge based on factual and theoretical knowledge. It is the result of thinking not about ‘what’ but ‘how’, and competitive businesses or individuals possess such knowledge. We can call these knowledgeable individuals truly smart. Considering ‘how’ in problem-solving or decision-making can be regarded as intelligence since intelligence is the ability to find rational adaptation methods when faced with certain situations. When intelligence in a field becomes more generalized and combined with creative thinking to do something different or new, we call it wisdom.

Wisdom involves combining existing knowledge to find new derivative knowledge or applying it to other fields to create new theories or creative works. For example, knowing the price difference between discount stores and local supermarkets and the reason for it means you should go to a discount store to buy cheaper goods. This can be considered a form of consumer intelligence. However, it’s not necessary to go to a discount store just to buy a bottle of soda. Considering the cost and time opportunity cost of using a car, one should go to the discount store only for bulk purchases. This can be considered wisdom. Wisdom evolves when one piece of knowledge transforms into another derivative knowledge or when several pieces of knowledge are integrated.

If we were to represent the discussions so far as a figure, it would take the shape of a pyramid, known as the DIKW Model. From this model, we can derive at least three insights. First, as we move up the pyramid, the outcomes become simpler, but their value increases. Second, this simplification process aligns with the ‘principle of thinking’. Third, the simplification process does not happen automatically; it requires energy, that is, effort.

Although the classification of knowledge in a pyramid shape is symbolic, it is not merely conceptual. While it may lack precision, moving up the pyramid signifies a reduction in quantity. If we were to store given data, organized charts or information, analyzed and organized reports, manuals or guidelines for execution, and sentences expressing the core ideas on a computer, the stored capacity would sequentially decrease. In this case, the quantity becomes a concrete entity that can be expressed in bytes, not just a conceptual one.

Another point to consider is that while the capacity decreases and becomes simpler as we move up the pyramid, the value progressively increases. For example, wisdom is sometimes expressed in a single line, such as “Know thyself”. Although simplified, the value of such a statement is by no means small. Its value is something that can be actualized through action, and its application scope widens. Specific information may have significant meaning for a concrete task but lose effectiveness in other matters. Knowledge may be useful for similar tasks but lose value when applied to new fields. Wisdom, though simple, is knowledge enhanced with creativity and has a broad scope of application. Steven K. Scott, the author of “The Richest Man Who Ever Lived: King Solomon’s Secrets to Success, Wealth, and Happiness”, asserts that the difference between knowledge and wisdom is like the difference between reading a billionaire’s biography and becoming a billionaire oneself. At the pyramid’s apex, we encounter the world and derive outcomes from that place.

The pyramid narrows as it ascends. But why does the capacity related to thinking decrease as we move up? Although it may sound like a foolish question, it holds significant implications. The pyramid shape is not coincidental; it emerges because it aligns with the principle of human thought. We all have the capacity to absorb a vast amount of information, but our ability to process and think about that information is drastically limited compared to our storage capacity. Moreover, our short-term memory capacity, which comes into play at the moment of action, is minuscule. For execution, it is necessary to increasingly simplify. This is because of the way our brains function.

Information and knowledge become wisdom through simplification. Even a report spanning hundreds of pages ultimately gains value when simplified to a single conclusion. This is why Martin Fischer could say, “Knowledge is the process of piling up facts; wisdom lies in their simplification.” Simplification requires effort and skill, which could be termed the “art of thinking.” Indeed, we have learned various “arts of thinking” throughout our lives. While learning different subjects, we not only acquire knowledge in those fields but also learn as many ways of thinking. In music, we train how to “feel,” in art, we learn how to “imagine.” During math lessons, we practice deductive reasoning, and in physics, economics, and history, we learn the importance of inference.

To understand the world, all these methods are necessary. Through such processes, knowledge gained from various sources is refined into useful and simple wisdom. Philosophy is often defined as the “love of wisdom (philosophia).” Depending on what one investigates, the meaning of philosophy can vary greatly, but if loving wisdom means philosophy, then all disciplines include philosophy, and we are all philosophers.

The first step towards simplification is “organizing.” Taking the time to tidy up our cluttered desks and bookshelves can give a sense of accomplishment as if we’ve done something significant. Not everyone enjoys organizing all the time, but it’s a necessary process to begin any work. In fact, organizing itself constitutes most of the work and is the start of it. Or, organizing can be the work itself in many cases. Even if organizing isn’t the essence of the work, it often takes up most of the time.

The same applies to our thoughts. Organizing means bringing order among things, which in turn means systematizing. Organizing, which we’ll discuss later, involves finding order out of chaos. Such order contains “usable energy,” which is the value of organizing, ensuring its practicality and utility. The power of organization is found in objects, knowledge, information, natural phenomena, and social skills because they are all interconnected in networks and relationships.

Well-organized and systematized entities appear smaller, even though nothing has been discarded. Of course, one method of organizing involves getting rid of clutter, but even without discarding anything, organization makes things appear simpler and smaller. A neatly arranged troop of soldiers looks smaller than a disorganized group, although different formations can manipulate their perceived size. Anyway, a well-organized library holds more books. The same is true for our memory. Well-organized knowledge can be remembered in a smaller capacity, not that our brains are too small to worry about the capacity of knowledge.

There can’t be one single correct answer to organizing or systematizing, but there are essential elements to consider: relationships and principles. Organizing means determining the relationships between members based on principles, and ensuring those principles hold meaning. Whether organizing information and knowledge, structuring objects or businesses, or managing tasks, ultimately, the same method of organization is applied. Consider the pyramid of knowledge, which, when organized, converges to a single point, becoming increasingly simplified. From another perspective, it could also be seen as a structure that starts from a point and expands into many.

In such a pyramid, parts at the same level can be reorganized in various ways, with one of the simplest being categorization by topic, much like the table of contents in most books. For example, under constitutional law, civil law is divided into general principles, property rights, obligations, and family, based on topics. A topic essentially extracts the central issue from many discussions, which can vary depending on perspective and situation.

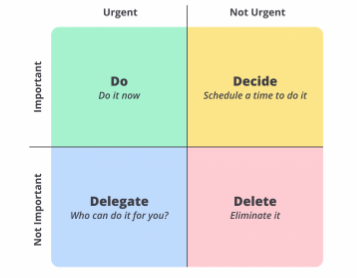

For instance, we could organize the problems we face by the importance of tasks. Just by doing so, our work efficiency could double. However, importance is just one of many characteristics of a task. We could also categorize tasks based on two factors: importance and urgency. As mentioned before, it’s this level of simplification that allows us to execute tasks efficiently.

Dwight David Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces during World War II and the 34th President of the United States, is called a master of simplification, and his method is known as the “Eisenhower Principle.” The principle is quite simple. Eisenhower is said to have divided his desk into four sections for tasks to be “discarded,” “delegated,” “consulted,” and “done immediately.” At the end of his work, his desk would inevitably be clear of everything.

If it were up to me, I would add one more category: “to wait for.” No matter how urgent, there are tasks that must wait for the right time to be accomplished. Such tasks must be kept privately, unknown to others. Then, after a day’s work, my desk would be left with only the tasks waiting for their “time,” anticipating their “turn.”

Knowledge is a process of piling up facts; wisdom lies in their simplification. ~ Martin Fischer

답글 남기기